The Czar of Public Art in Chicago

Lorado Taft, the City Beautiful, and the Hideous Columbus

I’m working on an article about Lorado Taft. I have bumped into him while researching so many stories that I thought it was time to take a look. I’m stumbling into so many stories I know I can’t go into detail in the article but seem worth sharing.

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition transformed Taft’s thinking and his influence. He became central to the City Beautiful Movement—the belief that good design and the right art could literally transform city life. One of the problems for the movement was what was then known as Lake Front Park. It was a strip of grass on the east side of Michigan Avenue, hemmed in by the railroad tracks leading to a massive multi-track freight yard on the Chicago River.1

For a time, the city thought that the 1893 World’s Fair could be held there, but the rights of the railroad and the rights of the harbor presented too many problems. There had been exhibition halls there, but the strip of grass along the east side of Michigan Avenue was also small and narrow. The fair headed down to the undeveloped and far larger acreage of Jackson Park and the Midway.

They did build one permanent building on the east side of Michigan Avenue. The “congresses” were held there—some of them were wildly influential and all were popular, like the famous Congress of Religion. The reason it was permanent was that the trustees of the Art Institute intended to move in after the fair. They had been in the smaller building across the street at Van Buren on the southwest corner.

I’ve known all that a long time, but I had never ever before encountered mention of the supposed permanent monument to the fair—a statue of Columbus in Lake Front Park, opposite where Congress Parkway ended at Michigan Avenue.

At first, I thought it must have been one of the current Columbuses (Columbi?) that became controversial in 2020 and are currently in storage or under wraps. Of course during the fair he was everywhere. The current three are a rotund Columbus that stood in front of the Italian building in 1893 and was in an Italian neighborhood afterward,2 a slim Columbus that was part of the Drake fountain downtown in 1892 but later wandered down to the South Side, and the massive Columbus that welcomed people to the 1933-1934 Century of Progress Fair on the south end of what would become Grant Park in an homage to the earlier fair. The 2020 attempt—undoubtedly dangerous—to pull down the Grant Park Columbus produced a commission that examined the nature of public art and produced a set of recommendations.

I found the questions at the meetings interesting. As some of you might have noticed, I’ve been looking a lot at public monuments—why they were erected, the message they were meant to send, the message they send now, and the big question of who is the public in public art. 3

Part of the discussion was how to include the quality of the object as art in the discussion, but I’m not sure any of the current three Columbuses qualify as great art.4 But apparently none of them were as spectacularly awful as the Columbus that was unveiled across from Congress Parkway in March 1893.

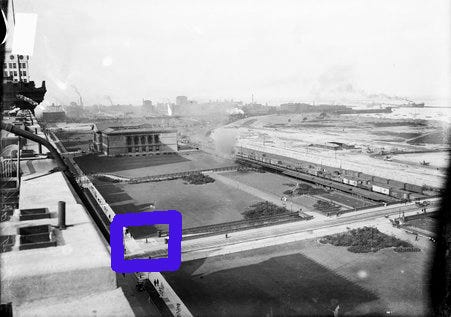

Why a statue in an empty expanse of grass? It was there because wealthy Ferdinand Peck, the man who hired Adler and Sullivan to build the Auditorium Building, was furious that the fair wasn’t going to be across the street. I suspect this 1907 photo shows the remains of where it once stood, though I think the extension of Congress Parkway happened later. You can see the charming backdrop of freight trains and rubbishy landfill in the undeveloped park even 14 years later.

The managers spent $50,000 (a shockingly high cost, close to $2 million in 2024 dollars) to appease Peck. He got to pick the artist after a “contest” and chose one of his friends, a tenant in the Auditorium Building—Howard Kretschmar, a sculptor visiting from St. Louis. At the ceremony, there was a lot of palaver about leaving a permanent reminder of the fair that would last down the ages. Everyone was polite until Ferd Peck’s daughter pulled the rope and it was unveiled.

There was Columbus, all 10 tons of bronze of him, 20 feet tall, atop a 30-foot granite pedestal. The artist himself said he didn’t attempt to model any known images of Columbus. He’d looked at photos of some famous actors to develop an ideal expression, which he himself said was a mixture of confusion, astonishment, determination, and benevolence.

Within weeks, the Chicago papers threw off any pretense that this guy wearing booties and a bathrobe was a worthy addition to the blank expanse of Lake Front Park. The Scandinavian, serving the large Swedish population, declared that “it is a brass man and that is the best that can be said about it.” They thought he looked like Dickens’s description of Mr. Pickwick—a lemon resting on two matchsticks. By May 9, 1893, a letter to the editor in the Tribune fussed that Chicago would be a laughingstock because “the figure looks like that of an escaped lunatic in a gale of wind.”

After the fair, the City Beautiful movement kicked in and there were meetings of very serious people discussing what should be done about Lake Front Park. A journalist at the meetings reported that every mention of the statue was met by derisive laughter. By 1897, the Chronicle was demanding that the “hideous incubus of the lake front” be taken down to rise no more.

As soon as control of Lake Front Park was given to the South Parks Commission, they tore down the statue and dumped it in the mud behind the horse stables in Washington Park among, as the Chronicle noted, the scrap junk and the broken sprinklers. The Tribune said that they were sure that it was mere coincidence that the fish stopped biting as soon as he was dumped in the park.

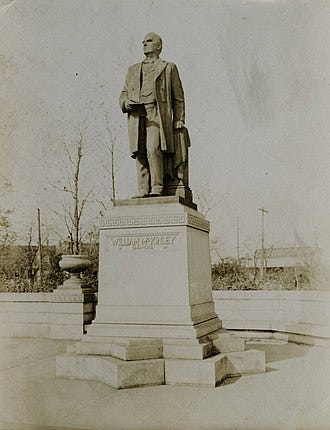

Menasha, Wisconsin, got wind of his fate and asked if they could have the unloved Columbus, though they didn’t want to cover the $50,000 loss. Instead, Columbus slept among the rubbish until 1902, when the South Parks Commission decided to recycle the bronze. They managed to salvage $3,000 by turning the bronze into a statue for William McKinley Park in honor of the assassinated president.

And what does all this have to do with Lorado Taft? The horror of Kretschmar’s Columbus was so great that the Inter Ocean among others demanded that the city create a Municipal Art Commision to decide what art the public was forced to look at. The city agreed and created an eight-member commission consisting of the mayor, the president of the Art Institute, the presidents of the three park commissions (North, West, and South), and three experts.5 Two were men who had collaborated on the Horticulture Building in 1893—architect William Le Baron Jenney and sculptor Lorado Taft.

The newspapers made it clear that the commission’s mission was to prevent anything like Kretschmar’s Columbus from happening again. And with that, Lorado Taft rose to real power as the czar of public art in Chicago, though, as the Illinois Historical Art Project says, he was “a genial czar during his long reign in the sculptural affairs of Chicago.”

The magazine for smart young things in the 1920s and 1930s, The Chicagoan, mocked the idea that art, especially neo-classical art, could make a silk purse out of the sow’s ear of Chicago, but he did manage to prevent anything so awful that people insisted on tearing it down in just four years.

Millenium Park is actually a foam structure over the top of the mostly unused railyards that became underground parking. On top of the foam is the topsoil that sustains Lurie Gardens and the Pritzker Pavilion and all of the interactive art of the park. It proved the point, with a very un-Beaux Arts design, that public spaces could transform the energy of the city.

It has a lot in common with this one, but deeper digging in the newspaper archives proved that there were two rotund Columbi with hands on their chests.

The fair should be remembered—it literally changed history—but none of the Columbuses do that. They are still out of sight because Columbus the man and Columbus the symbol are both bad—unless one is Italian. History resurrected the facts that he was regarded as a heinous criminal even by the standards of his own time. The Statue of the Republic is the better representative of the fair in all its complex messages, good and bad.

I do rather like the skinny Columbus who hung out on the Drake Fountain, but don’t find the other two appealing.

The parks commissions were independent agencies authorized by the state to charge taxes and make decisions about the parks under their jurisdictions. The Municipal Art Commission could make recommendations to them but couldn’t dictate to them. The commission could dictate what happened elsewhere in the city. The third expert was painter Ralph Clarkson.

Any thoughts given to LT’s art studio in downstate Elmwood, Illinois?