Chicago has been the host of many political conventions and Hyde Park has been connected to at least three of the famous ones. The first was 1860 and the Republican convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln. Hyde Park was a central location of Lincoln supporters and even his friends and associates. In addition, the very new Hyde Park Hotel, billed as a hotel as luxurious as any in the east, provided a home base for quite a few of the 400 delegates. The convention meetings were being held in a temporary structure at Lake Street and what is now known as Wacker. There’s still a plaque there. This was the end of the line for the Illinois Central Railroad, so the delegates staying at the Hyde Park Hotel had a fast trip from the 53rd Street station to the convention and they could stay among fellow Lincoln supporters. The ICRR ran special trains to get them back and forth on schedule.

Of course, the 1968 Democratic Convention is Chicago’s most famous. As a liberal bastion and university campus, Hyde Park provided a base for a number of the participants in the protests and a home base for the defense team of the Chicago 7.

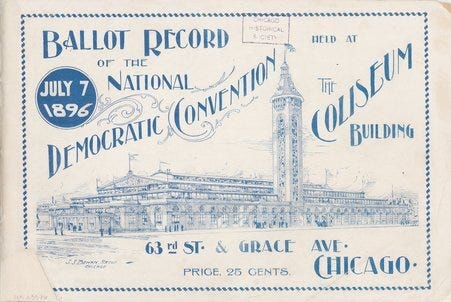

And I just stumbled into the third—the 1896 Democratic Convention that nominated William Jennings Bryan. Earlier this week, I’m reading an article in the Chicago Tribune that is giving the long past history of Chicago’s many political conventions when I see the off-hand statement that Bryan’s convention was in the Coliseum at 63rd Street and Stony Island. What the heck?! I’d never heard of such a thing.1

I of course have encountered William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech. I learned about it as a plea from debt-ridden farmers to have a larger money supply. I learned more recently about the brutal depression in the 1890s. There were many who hoped for some kind of relief from the misery. Switching to a silver base for the value of the dollar and away from gold would loosen the flow of money through a society that had no safety net. At the convention, Bryan cried out, with his arms spread wide: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” That got him the nomination though he was only 36 years old. The Chicago Tribune pointed to the stakes that needed to be addressed just ahead of the convention.

But why were they meeting down here? It turns out they were meeting in a building I had never heard of, mostly I suspect because it had a very short life. But it presented a lot of fun sidelights on the times, so I’m going to do another newsletter on it.2

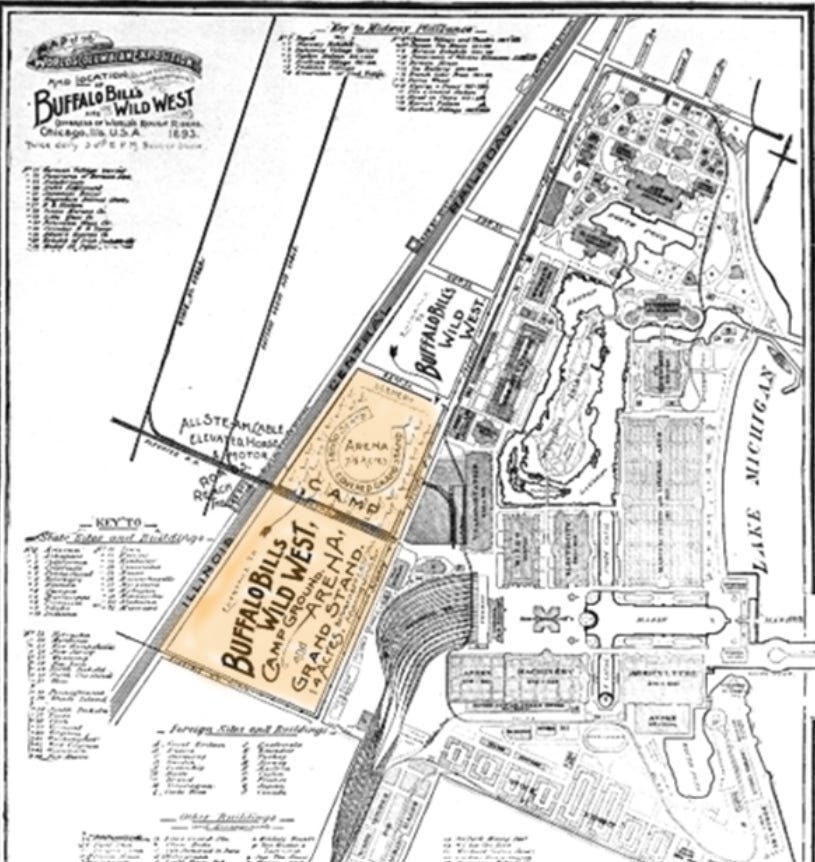

The Coliseum corporation began building the exposition building in 1895 on the 14-acre site that had been occupied by Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show during the exposition.3 I’ve marked the location of the Wild West Show in yellow here. It’s the space between 62nd Street and 63rd Street, the ICRR tracks and Stony Island Avenue.

The corporation hired Solon S. Beman to be the architect. He was famous for many buildings around here—some of the Rosalie Villas, Pullman, and the Blackstone Library—but I’m sure what interested the corporation was his experience as the architect of the Mines and Mining Building at the fair. It was famous for its open central floor, free of any pillars. They wanted to build a permanent building in the same style, with a massive ironwork frame, a glass roof, and a lot of acreage. They enclosed close to seven acres of floor space. They claimed that it was the largest indoor space in the world. The Inter Ocean newspaper described the style as Italian Renaissance with “massive simplicity and graceful proportions.” The first floor was buff brick around an arcade of large arched windows. The campanile was 240 feet high with an observatory and a café on top.4

The rest of the grounds were called the Coliseum Gardens and provided outdoor entertainment, particularly extravagant pyrotechnic shows. The Illinois Central Railroad, the “L” Alley Elevated, and the Chicago City Railroad (cable and street cars) all invested in the enterprise because they anticipated carrying thousands to the shows. After the 1893 fair, their south side numbers were down.

In 1895, the Coliseum corporation had a contract with the massive Barnum and Bailey Circus so they were rushing to completion when disaster struck. First, early in August, one of the girders, overweighted, twisted and turned. Two men who were working on it, 150 feet in the air, fell to their deaths. They weren’t sure why that had happened. Then, on August 21, around 30,000 feet of heavy green lumber were resting on one girder, which was not designed to take that concentrated weight. It bent over, starting a domino effect that took down the whole structure. Ten of the eleven roof trusses fell into a twisted mass of worthless iron. The electrical wires already installed electrified the steel trusses. Luckily, it happened at night when the evening crew had gone home. No one was hurt. The crash was so loud that people jumped off the streetcars as far away as 43rd Street, trying to figure out what had happened. As always in the turmoil of the 1890s depression, the first theory blamed tramps.5

The circus was left scrambling to find as large a space and the many possible shows and athletic contests that had lined up were out of luck. Though they papers quickly agreed that it really had been the bad judgment to put extraordinary weight on one girder, the Tribune was scathing in its criticism. They accused the corporation of “gross carelessness” and “criminal inattention to duty.”6 They also ran a cartoon of an aged intact Roman Coliseum staring down at a toddler sitting in rubble.

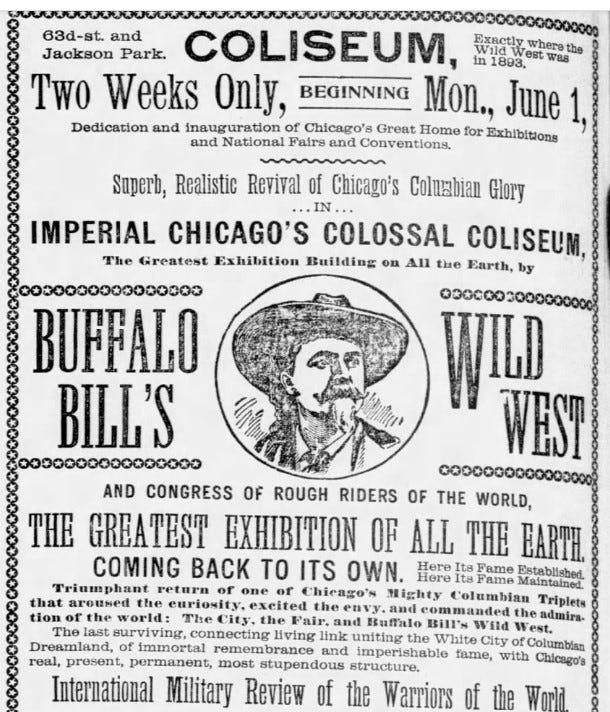

The corporation immediately threw itself into the task of starting over. And fairly soon got more contracts for use of the space. One of them was the return of the Wild West Show itself, bigger and better than ever. When he was asked whether he had concerns about the building, Buffalo Bill replied “I expect to give the people of Chicago a show that will open their eyes.”7

The corporation put in the bid for the Democratic Convention. Many people across the country kept objecting to the fact that it was seven miles from downtown, but the organizers pointed to the excellent transit network—and of course the centrality of Chicago in the national railroad grid. The committee agreed and the race was on to get it built in time. They set hundreds of workers on the task, a blessing for workers during the depression. And just managed to squeak by in time for Buffalo Bill. Tens of thousands came to two shows a day and gave the show a profit of $35,000 to $40,000 a day. A bad storm swept through and proved the Coliseum building was sturdy, waterproof, and windproof.

The building passed muster but the organizers of the Democratic Convention did not. The Missouri politician who was the Master at Arms in charge of security put his political heelers in charge of the one door. The Coliseum had 17 doors, but they were allowing entry only at the one. So delegates and spectators arrived by the thousands, just 14 minutes on the ICRR, 20 minutes on the street car, and then stood for hours outside in the pitiless sun without water or rest. Women raised their umbrellas to create a little shade and to save their hats from the coal cinders that came flying off every passing train.8 Some women fainted after two hours on line.

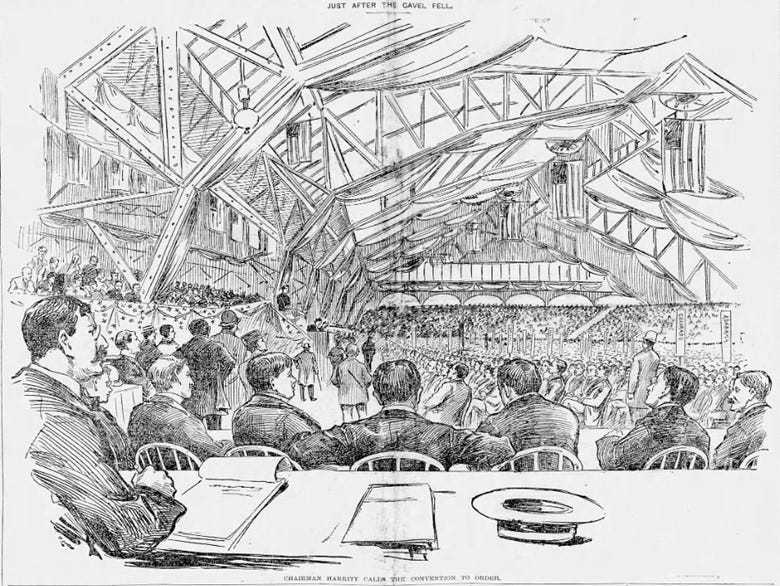

The newspapers skewered the organization, pointing out that the most prominent men in the country were left kicking their heels. Even Illinois governor Altgeld couldn’t force is way in. When he tried, an out of towner said, go away, whiskers. Newspapermen tried to take matters into their own hands and “marched seven times around, but unlike Gideon at Jericho, the doors didn’t fall down.”9 Two thousand delegates, 15,000 spectators, and quite a few members of the press were allowed in four every minute. Once inside, they had to show their credentials again to several more layers of security, but once inside they were left on their own devices. If they found an usher, he just blushed painfully, gestured vaguely at the vast expanse, and muttered “down there.”10

The delegates were on the flat central floor in front of the speakers stand. One reporter said the vast space and immense crowd felt like a landscape. From his perspective the floor seemed like a flat valley marsh. The tops of the delegates heads were so far away they blended together, interrupted by the sign posts of the various states like blue bullrushes in the expanse. A lone policeman on the far top southwest corner seemed like a condor perched on the crest of the Andes. There were hilariously bad large charcoal sketches of past Democratic presidents, including some of the ones you might rather forget, like Buchanan. There was one no one could figure out.

I’ve seen accounts that say that Bryan couldn’t be heard during his great speech, but the newspapermen on opening day were struck by how good the acoustics were in such a vast space. Of course, this is before any kind of amplification.

One of the great blessings, which the delegates to this year’s convention are experiencing, was great weather. In the days before air conditioning, Hyde Park offered the breezes off the lake, which can drop the temperatures 10 degrees. The indoor temperature was in the mid 70s and a light breeze through the opened glass roof made it while the speeches got heated.

The spectators were in the gallery wrapped around three sides. There was a section in the gallery just for the wives and “womenfolk” of the delegates. While Bryan may have been announcing his Populism, the Democrats were very much the party of segregation. The opening piece the band played was “Dixie” to loud whoops of joy. Just four days earlier, the Coliseum had hosted a large memorial concert to Hyde Parker George F. Root, the author of “Battle Cry of Freedom,” an anthem and great marching song that featured in one of Kamala Harris’s recent rallies.11

Ron Grossman, Chicago Tribune, August 11, 2024.

Just found out there’s a book about Chicago’s conventions written ahead of the 1996 Democratic Convention. It’s called “Inside the Wigwam: Chicago Presidential Conventions 1860-1996) by R. Craig Sautter and the now disgraced and conviced alderman Edward M. Burke. I haven’t read it yet, but I’m going to track it down.

I wrote about Buffalo Bill and Susan B. Anthony in this newsletter https://patriciamorse.substack.com/p/buffalo-bill-and-susan-b-anthony

Inter Ocean, August 5, 1895

Tribune June 30, 1895

Tribune August 23, 1895

Chicago Chronicle feb 11, 1896.

Inter Ocean July 8 1896

Tribune July 8 1896

Tribune July 8 1896

Fascinating!