I watched the Oppenheimer movie last week so took a look at the University of Chicago archives, since we had a cameo in the movie. I found some photos I thought might be interesting.

First off, I found an award ceremony in the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures auditorium [nee the Oriental Institute] where General Groves presented the Medal of Merit to Enrico Fermi and four others who weren’t in the movie. I thought it was a bit on the nose to perform the ceremony in front of a mural depicting the ruins of a civilization.

The ceremony was in 1946, seven months after the bomb. Fermi, of course, led the team at the univerity that built the first nuclear reactor that proved Los Alamos was worth the gamble. Fermi continued to have a critical role in creating Trinity, though he doesn’t show up much in the movie, which is too bad because he apparently had a very cinematic comment just before the Trinity test. They really weren’t quite sure, up to the last, what would happen.

The U.S. Department of Energy webpage on the Manhattan Project explains that he was there:

Fermi also became increasingly involved with the Los Alamos laboratory and the design and development of the bomb itself. Fermi took part in the opening conferences in April 1943 at the new lab, discussing the pile and its uses, and contributed substantially to the lab plans for physical investigations. Oppenheimer, director at the lab, made Fermi an associate director in July 1944 overseeing the research and theoretical divisions and all nuclear physics problems. …Fermi also was present at the Trinity test, where Groves became "a bit annoyed" when Fermi jokingly offered to wager "on whether [the Gadget] would ignite the atmosphere, and if so, whether it would destroy New Mexico or destroy the world."

By the way, in the following, I’m relying heavily on Wikipedia for the science. I’m not a nuclear physicist!

In checking that this was the Oriental Institute, I discovered that the public really had no idea what nuclear energy might become. Fermi gave a speech to the public in March 1946 explaining that the people thinking there would be atomic automobiles were wrong—the cars would weigh 100 tons because of all the lead shielding that would be necessary.

Interesting to me is that the team that achieved the nuclear reaction had reunions. Here’s the 4th anniversary. Fermi is on the front row. The only one who makes much of an appearance in the movie is Leo Szilard, who is the one in the tan raincoat on the right side in the second row.

This 1946 photo appeared in Life magazine. And yes, that’s a woman. She’s Leona Woods Marshall. Her Wikipedia entry is fascinating. She got her BS in chemistry at 18 at the University of Chicago and went on to the graduate program, working with Robert Mulliken, later Nobel Prize winner.

A few newsletters ago, I talked about the Point swimmers. Well, here’s where they enter history. Leona swam regularly in Lake Michigan and it was there that she met a fellow swimmer, Herbert Anderson, who was working for Fermi. When Anderson found out that she was just finishing her PhD with Mulliken and that vacuum technology was part of her thesis, he enlisted her to work on the boron trifluoride detectors used to measure neutron flux. Laura Fermi recalled that Leona at the time was helping her mother run the family farm in La Grange, Illinois, splitting her time “between atoms and potatoes.”

After Pile 1, Leona went with Fermi and her new husband Marshall to Hanford where they were manufacturing the plutonium for the bomb. Leona worked the night shift with Fermi, monitoring the reactor. When the reactor unexpectedly powered down, she was one of the ones who solved the mystery. In other words, Oppenheimer could drop the balls into his glass bowls measuring the manufacture of plutonium in part because of Leona.

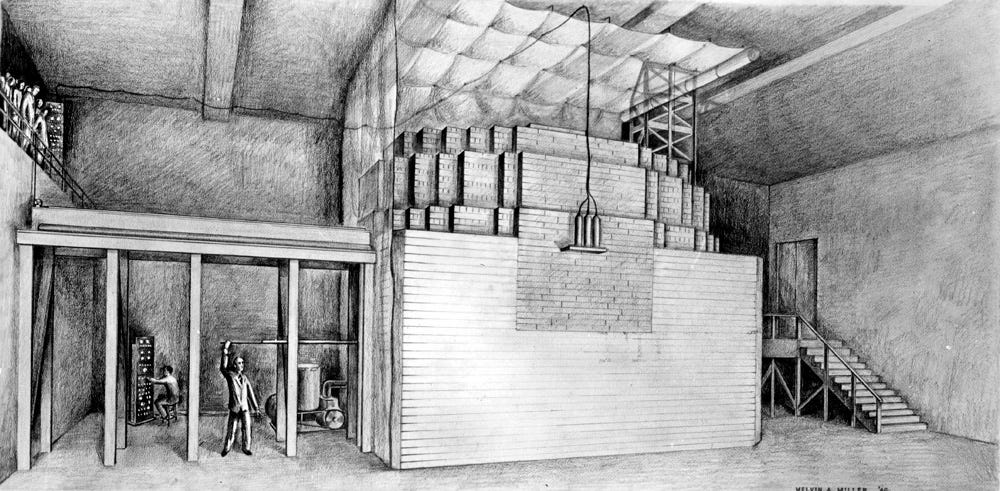

Leona was a squash player, so she was very familiar with the court under the west stands of Stagg Field. Here’s a drawing of Pile 1 in the squash court.

The reactor consisted of uranium and uranium oxide lumps spaced in a cubic lattice embedded in graphite. In 1943, it was dismantled and reassembled at the Argonne National Laboratory—with a pit stop in the Washington Park Armory, which I mentioned in my article about the Armory. There are lots of rumors about parts of campus that are radioactive, but that was a space that definitely was.

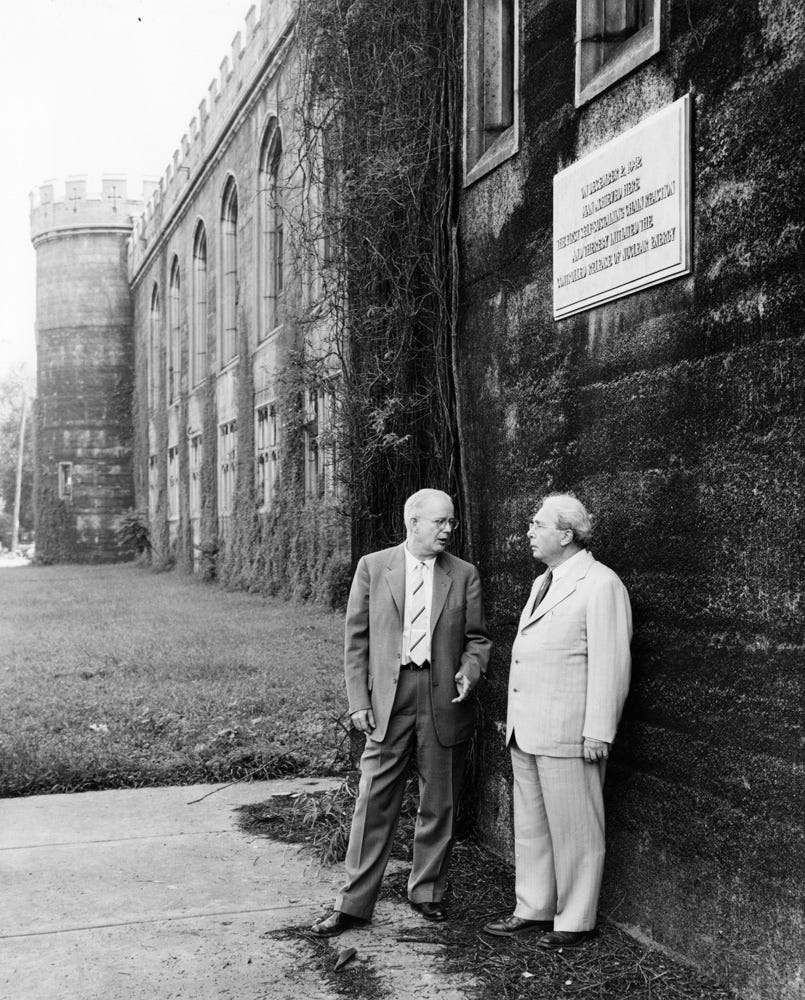

Here’s a photo of Leo Szilard outside the West Stands of Stagg Field, beneath a commemorative plaque. If you are wondering why the University of Chicago had a giant football stadium and why the football stadium was empty, check out my article on Stagg Field.

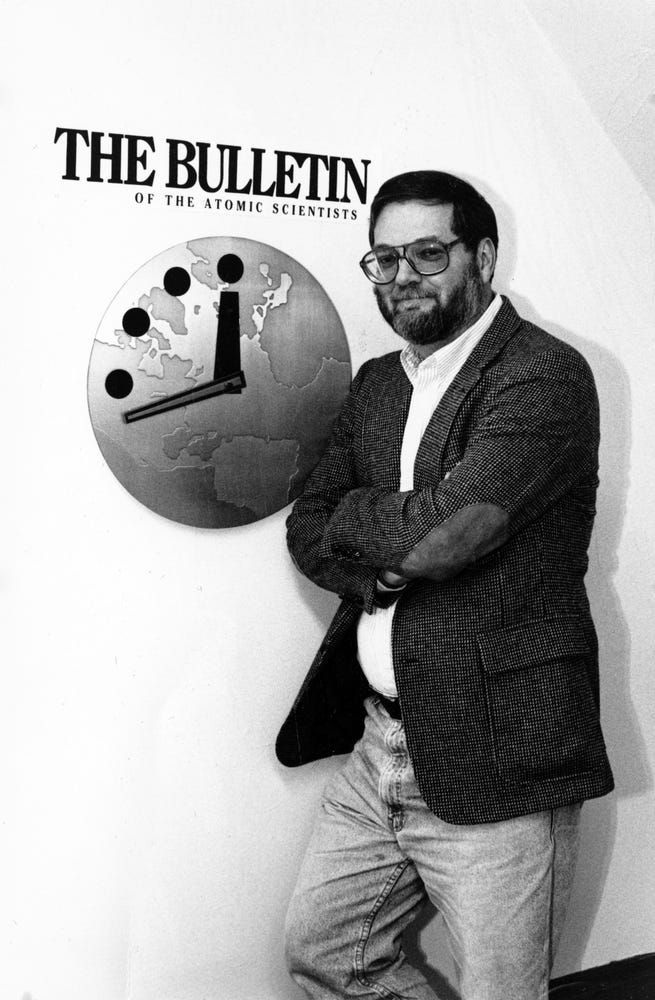

Szilard appears twice in the movie—first with Fermi under the football stands and second when he tries to get Oppenheimer to sign a petition about the scientists’ concerns about the coming arms race. Nuclear weapons quickly became a central concern on the University of Chicago campus, the home of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, who, to communicate with the public their concerns, invented the Doomsday Clock in 1947.

The clock is a metaphor for how close we are to manmade global catastrophe. The current clock, whose main factors now are nuclear risk and climate change, is set at 90 seconds to midnight. That’s not good. In 1991, in the photo, it’s four minutes to midnight. When Pile 1 went critical, Leona Wood turned to Fermi and asked, "When do we become scared?" The answer is now.

In the movie, the scientists debate the ethics of developing the hydrogen bomb. which was hundreds of times more powerful than the fission bomb dropped on Japan. Once Russia detonated a fission bomb, Truman authorized work on the H-bomb and the arms race on, known as MAD, Mutually Assured Destruction.

People forget how much this permeated every day life. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, I was 10 years old in a suburb outside Albany, New York. They showed photos of the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We repeatedly did drills preparing for the H-bomb to drop on us. We did drills of diving under our desks and covering the backs of necks with our hands to block the shattered glass. We went out into the windowless hall to do the same thing in case we had a bit of warning. One time we did a Go Home Drill, where we lined up, not by grade, but by where we lived. I guess they thought if there was enough warning we could go home to die with our parents, if our parents were home.

The home improvement fairs were full of DIY bomb shelter displays. I once asked my dad, What do we do if the bomb comes? My dad, the World War II veteran replied, Be at ground zero. I suppose it’s no wonder I had nightmares.

This is a photo of the University of Chicago Outing Club organizing a very different drill in 1954. They are planning a 19-mile hike to Palos Park. Atomic scientists told them that it was a reasonable distance out of the city center to evacuate to, assuming a three-mile radius of total annihilation. The students wanted to test the time for evacuation if an H-bomb dropped in Chicago, assuming impassable roads. The leader is the man on the left, Dr. Jay Orear of the Institute of Nuclear Studies. Though his goal may have been to bring home the dangers of MAD, it didn’t have much of an impact. Five years later, the United States installed (already outmoded) Nike missiles in Jackson Park and other sites along Lake Michigan. I am, however, impressed that one of the women intended to walk 19 miles in penny loafers.

The date of the hike was May 23, 1954, four days before Oppenheimer’s secret security clearance trial began. An assumption at the trial was of course that it was Un-American to criticize the logic of the H-Bomb. In another ten years, we had Dr. Strangelove.

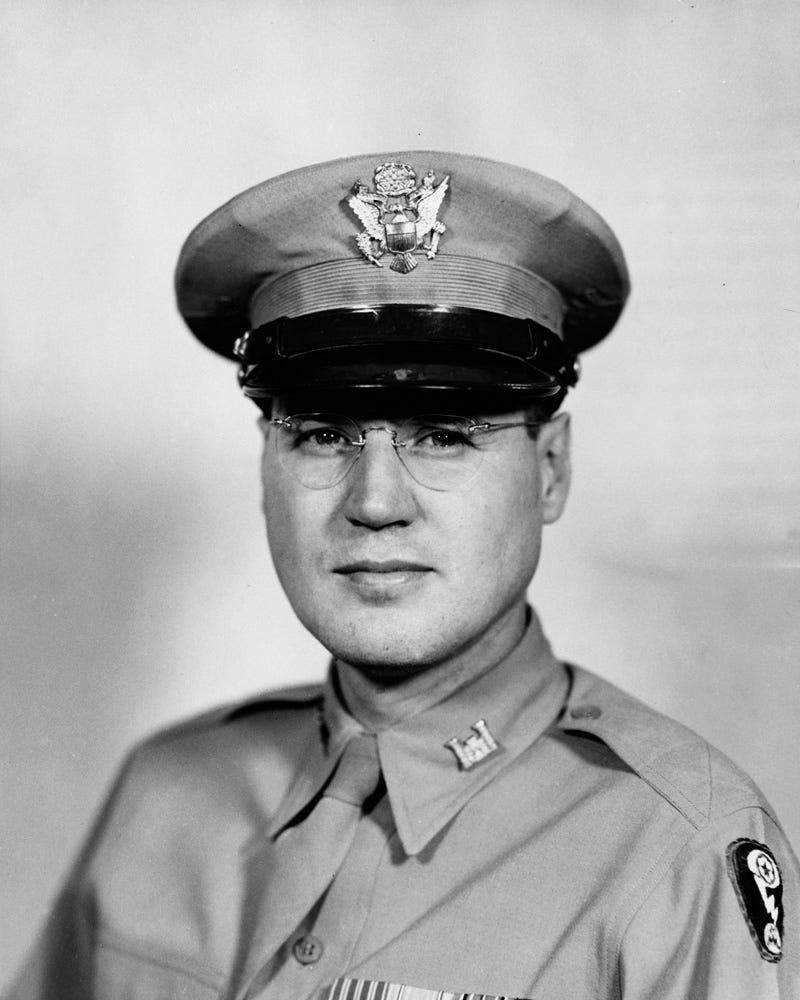

And finally, the archive mysteriously had a photo of the villainous Kevin Nichols, who collaborated with Strauss in his visceral dislike of Oppenheimer. Christopher Nolan not only tapped great talent for the movie but found it in actors able to capture the flavor of the original men, no matter how much they don’t look like the originals normally. Dane DeHaan, who plays Nichols, really doesn’t look like him ordinarily but transformed into him in the movie.

Agreed. Enlightening -- and fascinating back stories. And yes - the irony is not lost regarding the map at ISAC (nee the Oriental Institute) that appears in the photo of General Groves and Enrico Fermi. Thank you for all this research.

Very enlightening! These insights and anecdotes enhance the chapter for me. Thank you!

Personal note: My folks bought our apt on Blackstone & 58th from the widow of Fermi team member Sam Allison. 1967/68.