Mysteriously, this Substack has gotten a number of new subscribers. Hello! My main projects are recovering the history of Hyde Park, Chicago, especially as it illuminates American history writ large, and a book recovering my parents’ experience in World War II, written and researched with the idea of helping others recover the experience of their parents and grandparents.

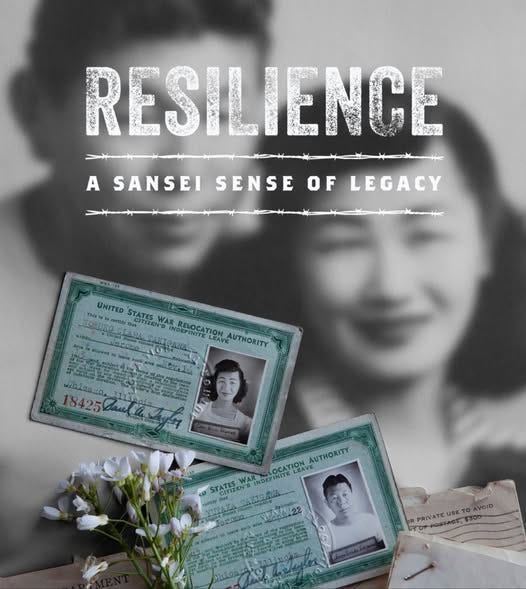

And, sometimes, as in this newsletter, my projects overlap. In pursuing my father’s wartime experience, I met the Friends and Family of Nisei Veterans and learned so much more about the Japanese experience in America. Right now, there are two ways folks can learn more about the connection to Chicago: an exhibit at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie and the video of a talk recently given at the Hyde Park Historical Society.

The exhibit at the Holocaust Museum reflects the artwork of later generations processing the generational trauma of World War II. I found the use of clothing imagery in a number of the artworks particularly interesting. There’s a particularly moving video of interviews with those who experienced the incarceration as children. It’s part of the decades long battle that people with Japanese ancestry have fought to have their story told. The exhibit is there through June.

This experience came on the heels of the Hyde Park Historical Society presentation about the life of Kiyotsugu Tsuchiya, who was the curator of the Harding Museum. It’s a fascinating and moving look at his experience but also the museum itself, which was a beloved and eccentric Hyde Park institution. If you’ve ever checked out the armor in the Art Institute, you caught a glimpse of the Harding Museum.

I have it on my list to write up as much of a coherent history of the Japanese and Japanese-American experience in Hyde Park for the Herald as I can because the experience in Hyde Park encapsulates so much of the larger history.

The first noticeable presence appears in the 1890s. People welcomed and embraced Japan’s presence at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. I helped transcribe a diary that’s in the Newberry that was kept by a north side woman during the 1893 fair. She came down to the fair several times a week all summer and almost always stopped to chat with the head of the Japanese section in the Palace of Fine Arts, often having tea at the nearby Japanese teahouse with him. Even the usually racist American newspapers had complimentary words for the Japanese at the fair. The fair seems to have inspired a number of Japanese entrepreneurs and entertainers to come to Chicago. The few who settled in Chicago tended to stay in Hyde Park and Woodlawn near Jackson Park.1

The University of Chicago, which opened in 1892, had early ties with Japan.2 The first person to earn a graduate degree of any kind from the university was a Divinity School student from Japan named Eiji Asada. In its efforts to rapidly modernize, the Japanese government sent a number of students to the university. One of them was Heita Okabe who studied with Amos Alonzo Stagg. Soon there was a baseball exchange program between the University of Chicago and Waseda University in Tokyo. In addition to the scattering of students, the University of Chicago welcomed a number of speakers and faculty members. The first faculty member was Shinkichi Hatai, an assistant in the Neurology department, who had graduated from the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1897.

In 1903, William Rainey Harper, first president of the university, found a position for Toyokichi Iyenaga to lecture on East Asian history and politics. An interesting account of him at Hull House is worth the read. It also describes the depth of racism fomented during World War II even far from the Western Exclusion Zone.

But the United States was legalizing its prejudice, first with the Chinese Exclusion act. To avoid exclusion, the Japanese government agreed to restrict immigration to the United States in 1907. But in 1924, the immigration act that created the bureaucratic nightmares for so many around the world barred Japanese immigrants from becoming citizens. Though there were thousands of Japanese and Japanese-Americans residing in the Hawaii Territory and on the West Coast, before World War II, only a few hundred people of Japanese ancestry lived in Chicago.3

In Hyde Park, the Century of Progress World’s Fair of 1933-34 produced a revival of interest in all things Japanese. There was a Japanese restaurant at 3725 S. Lake Park run by a Mrs. Tomiye Shintani. And the wife of Harding Museum curator Kiyotsugu Tsuchiya opened a Japanese restaurant in Hyde Park at 5253 S. Cornell.

The fair brought the creation of the Japanese stroll garden and teahouse on Wooded Island next to the original 1893 Ho-o-Den pavilion, a gift from the emperor to Chicago. I’ve written a brief history in the Herald.

And about its fate during and after World War II

The complex was the creation of Shoji Osato, a photographer married to an Irish-American woman from Kansas. There were enough Japanese-American women in the neighborhood that he could hire waitresses and staff for the complex. Visitors enjoyed green tea, tuna sashimi and American sandwiches while absorbing the beauty of the new garden. Afterward, they could visit the glorious art inside the pavilion.

With the bombing of Pearl Harbor, it all changed. Suddenly, the news is full of hate and loathing, even in a small paper like the Hyde Park Herald. Shoji Osato was arrested even though he was living outside the Western Exclusion zone. He was a Japanese citizen (because he had no ability to become an American citizen) who was celebrating Japanese culture. That made him the enemy. He was incarcerated first in a house on Ellis Avenue and then in a camp in Wisconsin.

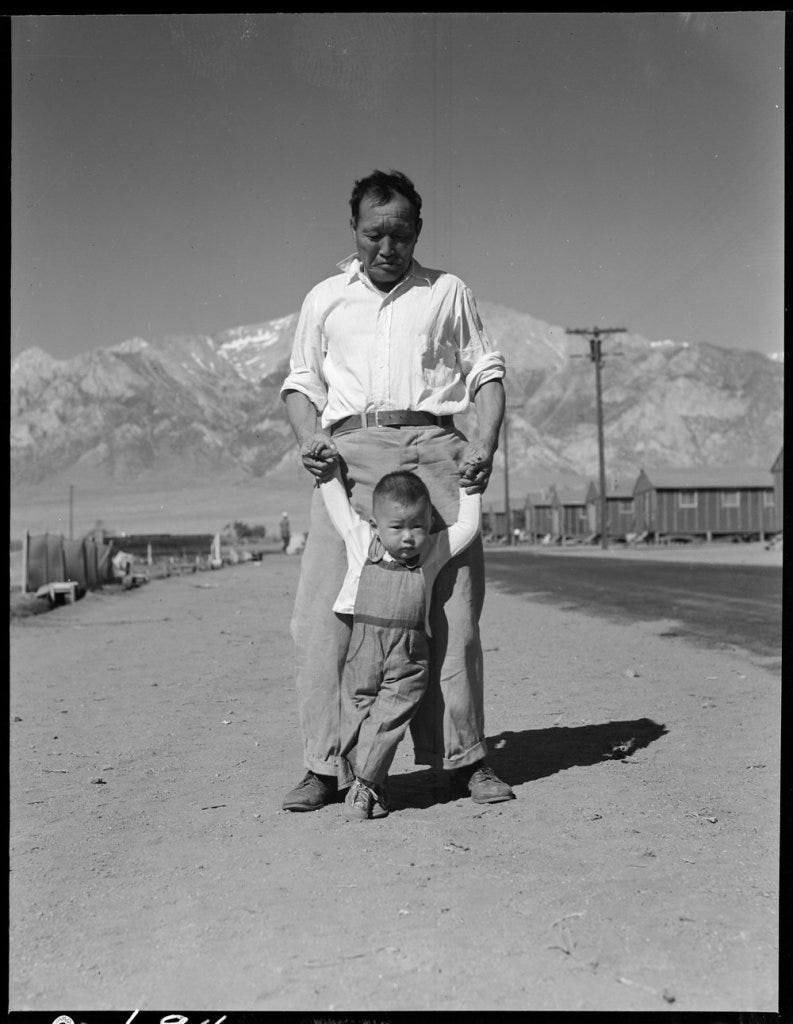

The most horrifying breakdown of basic civil liberties happened in the West Coast Exclusion Zone when anyone of Japanese ancestry—including U.S. citizens—was rounded up without due process due to the hysteria whipped up in the Hearst newspapers. Forced to sell everything on short notice, people were financially ruined. They had to abandon their whole lives with absolute uncertainty about the future.

For the nation, they were out of sight and out of mind. Cameras were forbidden. Photos were seized during the war, including the photos by Dorothea Lange, who was fired for being too honest in documenting the relocation. There was happy propaganda, but images of the reality weren’t rediscovered for decades. For the people, the future was of course barbed wire, machine gun wielding guards, and a complete lack of privacy or physical comfort. The residents were trapped in desert landscapes in tar paper bunkhouses. They recreated lives there as best as they were able.

The government knew from the start that the conspiracy mongering wasn’t true. It was just politically expedient. As a result, it wasn’t long before U.S. citizens were given some opportunities to leave. Young men were asked to fight in the Nisei-only 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which became the most decorated unit of that size in World War II. College students who had been studying at schools like Berkeley could attempt to transfer to schools outside the Exclusion Zone, but many schools—including the University of Chicago—refused to admit them. Others could go to cities outside the zone if there was a sponsor. In Chicago, the Quakers in particular stepped up, and soon Chicago held the largest population of people relocated from the camps.

It was not the warm welcome that’s sometimes portrayed. At one reunion of the Friends and Family of Nisei Veterans, I was seated next to a lovely older woman, who, when she heard I was from Chicago, instantly teared up. Just the name recalled a time when she could find no job and no place to simply be. As the people released into Chicago grew in number, they created organizations to help each other find places to live and work. There was a group on the north side, but the largest was in Oakland/Kenwood just north of Hyde Park. There’s a detailed map of stores and apartments here and a set of memories.

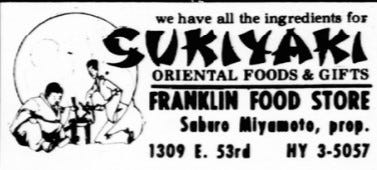

Quite a few spread south into Hyde Park and Woodlawn. The Buddhist Temple, which had an altar that came from one of the camps, was at 5487 S. Dorchester. Another group gathered along Maryland Avenue just west of campus. Several stores opened along 55th Street, including the beloved Franklin Food Store, which was opened at 1374 E. 55th Street. It supplied the kinds of fresh fish, vegetables, and rice needed to recreate familiar food. A 1946 directory lists it and other Japanese-owned businesses in the area. The Hyde Park Restaurant, serving Japanese food and the Chinese food familiar to the white residents of Hyde Park, was at 1464 East 55th Street. Lake Park Radio Service was at 1376 East 55th and at 5462 Lake Park. Paramount Cleaners was at 1445 East 55th Street.

After the war, quite a few people returned to the West Coast, but many settled in to stay, creating community organizations and joining existing ones. There was a Nisei bowling league and several baseball teams. They also, in Hyde Park, entered into existing community organizations like the Kiwanis and the churches. For instance, Rev. Michael Yasutake became the deacon and curate of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in 1950.

The Kenwood-Oakland community disappeared in the early 1950s as the rapidly increasing Black population of Bronzeville expanded south, tensions with the white population increased, and the first wave of urban renewal created intense competition for housing. The Japanese-American community’s roots were shallow and easily transplanted to the north side and suburbs. In Hyde Park, with the block club organizations created by the Hyde Park/Kenwood Community Conference designed to work toward a racially integrated, diverse Hyde Park, more of the Japanese community sought to stay.

Urban renewal, however, wiped out the areas in Hyde Park where the community had concentrated. The Land Clearance Commission and the Southeast Chicago Commission, which was the political wing of the University of Chicago (as SECC leader Julian Levi announced), designated two types of areas for demolition. If the buildings were deemed dilapidated or if the buildings were solid but the commissions decided the land should have a different purpose, the owners, businesses, and residents had no choice. The commissions determined a price, seized the buildings, and tore them down. For the Japanese, this was the second time that their government had betrayed them. The commissions leveled the 55th Street and Hyde Park businesses and quite a few of the Japanese-owned apartment buildings.

The commissions seized the Buddhist Temple and provided no means of relocation within Hyde Park—though all of the block clubs in the surrounding areas petitioned to allow it and its 400 members to remain in the area. There was no land use for a temple. The Buddhist Temple, often called the Buddhist Church, relocated to the north side. When the commission knocked down the area residences to create Nichols Park, people followed the temple out of the neighborhood.

When the university and the corporation it had formed decided to eliminate the blocks to its west, Black and Japanese-American residents fought back. St. Clair Drake, author of Black Metropolis, and Michael Hagiwara, a young lawyer, took on the University of Chicago and the constitutionality of allowing a private corporation to exert eminent domain over well-maintained buildings. Hagiwara had been in an incarceration camp when he’d enlisted in the 552nd Field Artillery as part of the 442nd. He’d fought in France and Italy, and then, reassigned, ended up liberating one of the camps in the Dachau complex. He’d come to Hyde Park after the war to get a business degree from the University of Chicago. He became a real estate lawyer. He’d formed a community center for southwest Hyde Park, served as a vestryman at the Episcopalian Church of the Redeemer, and joined the Kiwanis. He was exactly the kind of citizen you would think the “new” Hyde Park wanted.

It’s hard not to feel that the stress of the extended battle to defend his community contributed to his heart attack at the age of 36. The university won through a technicality after his death. The constitutionality was not tested.

Hyde Park’s Japanese-American community dissolved, though parts lingered. Displaced by the destruction of 55th Street, Franklin Foods moved to 53rd Street, where it survived under its new owners the Miyamotos until 1979. It was beloved by the children who attended St. Thomas Elementary and Murray School as a source of jelly candies wrapped in rice paper and colorful mochi. There were enough residents still who appreciated the sushi grade fish, great sacks of brown rice, ramen noodles, and imported foods and it served the diverse neighborhood, providing foods others found hard to find in the 1960s like fresh tortillas and food kosher for Passover.

The Japanese community of Hyde Park was, even in the 1980s and 1990s, committed to making Hyde Park a better place. In particular, we owe the Japanese Garden that so many love on Wooded Island to their steady efforts to bring it back to life.

Such a sad history. Invariably valuable assessment of HP story. Thanks.

Really appreciate how deeply you look into the archives, Trish! Best new yesr wishes.