Someone posted a picture of an intriguing building and described it as “hidden” and “forgotten.” As is usual on the internet, the comments were from north siders. South siders were irked.

For some reason the original poster never likes to provide an address of their photos and said there was no information. Once someone identified the address (roughly), I thought, well, I’m taking a break from my Herald article, let’s see if there’s nothing in my favorite source, the digitized newspapers, which so often but not always provide little glimpses of people’s lives. I thought it would be fun to share, especially since there’s quite a glimpse with this one.

The first thing I found was this in the April 9, 1893, Tribune:

It makes it clear that there were three townhouses in a row, built in the great south side World’s Fair boom of 1893. L. B. Wheeler, builder and owner, is very proud of them. Apparently, even though attached, all three were a bit different. Luckily, a comment online provided a photo.

4595 Oakenwald

Luckily for us, Wheeler didn’t sell 4595 right away, the one on the left, so he ran a fuller description:

To Rent—4595 Oakenwald-av., new 3-story stone-front ten-room house: specially designed hall tree, console, sideboard, china closets, and mantels; exposed nickel plumbing, steam heat, marble bathroom, and mosaic vestibule floor; servants’ bath in basement, incandescent electric lights. Finished throughout in various hardwoods, decorated bowls, very handsome hand decorations throughout. Only 2 blocks from Kenwood Station on Illinois Central railroad; fine view of Lake Michigan from this house. This house was not built to rent, but is first-class in every respect.

If Oakenwald isn’t familiar, it’s quietly right by the lakefront and not on the north-south grid as it follows the tracks and lakeshore slanting to the west. Before the landfill and turning Lake Shore Drive into a highway, it really would have had a view of the lake.

It seems to have worked because soon there was an ad for a Girl, general housework (must be competent). Sadly, the next year, their dog, a water spaniel named Daisy, ran away. No word on whether she was found and someone collected the award. In 1898, it was for rent again. In 1902, a death notice says Alice Middaugh, a single teacher, lived there, probably as a boarder with the Williams/Winchester clan.

By 1900, the townhouses had become a colony, apparently. At least, some of the addresses, 4595 and 4599, seem interchangeable over the next years. James D. Williams, who had a publishing company, and his wife along with his wife’s parents, a servant from Sweden named Auguste and a boarder who was a musician were listed in 4599, but a death notice in 1903 for the mother-in-law lists 4595. She had the somewhat amazing name of Wealthy—Wealthy Winchester.

The Williams’s also provide a lesson in double checking sources. According to Ancestry.com, they aren’t living on Oakenwald during the census. They are all living on Lakebend Rabbiteye. I guess 1900 cursive was just too much for the transcriber. Sadly, James’ wife died in 1913. Her name proved too much for the Tribune typesetter. She was immortalized as Ezadnah, a name that appears literally nowhere else, probably because she was Evadnah.

When I’m wandering, I always enjoy finding paths that cross. While researching Earl B. Dickerson, I encountered the actions of U.S. Attorney General Thomas Campbell Clark, who sunk Dickerson’s ability to serve on the Illinois Fair Employment Practices Commission and serving as U.S. Assistant Commerce Secretary because he arbitrarily decided that the National Lawyer’s Guild, which Dickerson led for a time, was a Communist front. It was indeed integrated and liberal, but it’s hard to say a wealthy corporate lawyer, however progressive, wanted to overthrow the system. It is true that one of Dickerson’s election campaigns was as a Progressive when it was a liberal off shoot of the Democratic Party running Henry Wallace for president. But in the 1950s and 1960s, as now, disinformation campaigns are effective.

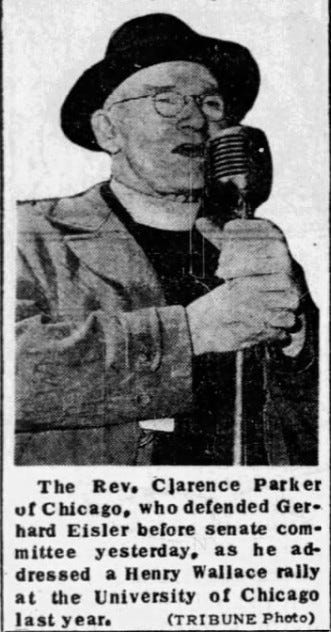

I crossed that path again because a resident of 4595 Oakenwald testified in the U.S. Senate that Clark should not be a Supreme Court justice. The Rev. Clarence Parker, recently retired as rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal church and current co-chairman of the Civil Rights Congress of Illinois, told the Senate committee that he opposed Clark’s nomination because of Clark’s “wicked and arbitrary” branding of the his organization as a Communist front. Apparently being a Wallace supporter was stain enough. Unfortunately, Red baiting didn’t disqualify Clark from serving on the Supreme Court.

The last mention of 4595 Oakenwald in the newspapers was in 2010, when taxes are owed by an unknown taxpayer for what seems to be the vacant lot.

4599 Oakenwald

The other missing building to the right in the photo, by the alley, was 4599 Oakenwald. It too was rented for awhile for $100 a month in 1894. By 1907, it was the residence listed in the obituary for Lee S. Harrison, the general superintendent of the Corn Products company, “one of the pioneers in the glucose business.” Apparently the company still exists as Ingredion, producers of high fructose corn syrup.

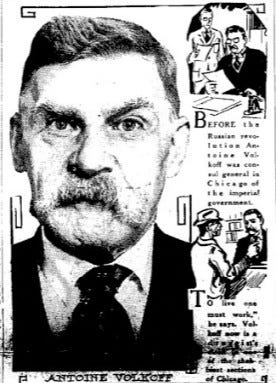

He’s not the most interesting resident. That has to be Baron Antoine Volkoff, former consul general in Chicago for Imperial Russia and the Kerensky provisional government. He seems to have lived on Oakenwald over the decades he was the consul general. An accomplished linguist, he served as an interpreter in Washington D.C. during conferences with Soviet representatives. When the U.S. recognized the Soviet Union in 1933, he was stranded. He became a U.S. citizen, worked in a drug store in Chicago, and was in demand by commercial artists and photographers as an advertising model because he looked so distinguished. He’d been a diplomat in Persia, Brazil, and Liverpool, before Chicago. Just before his death, he obtained a job at a west side war plant producing lend-lease material for Soviet Russia. The hard labor may have been too much for him. He was survived by his wife and two daughters, one who worked for the Department of the Interior in D.C., another a ballet dancer with the New York Metropolitan Opera, who was described as “slim and langorous.”

The papers reflect the changing demographics of the neighborhood. Unscrupulous real estate agents illegally converted large houses into small illegal firetrap apartments, which they rented to Black families who were hard-pressed to find better housing. In 1952, there was a near tragedy. Seven children and babies were found almost unconscious in a basement flat. Luckily, their teenage half-sister found them in time. A faulty hot water heater and oil burner had used up all the oxygen in the apartment. Their mother was at the welfare office trying to get help. By 1960, the city was asking for permission to demolish the now vacant 4599 Oakenwald.

4597 Oakenwald

Wheeler apparently sold the middle house, the one that survives, almost immediately to Charles Findley Eiker, an executive in the fireproof construction industry. They moved in from the Lexington Hotel. The Eikers were society page people. Their trips to Colorado, Mrs. Eiker’s luncheon for the wife of the Kentucky governor, and the black eye Mrs. Eiker got while in the grand stands of a tennis tournament were duly reported. Unfortunately, the player whose lob hit her was “thoroughly demoralized” and lost. What was also reported were the financial troubles they were in. Apparently he’d invested in the restaurant at the Casino Building at the 1893 World’s Fair, which had not done enough business. By 1900, the house was the property of Mr. and Mrs. F. A. Merriam. Within a year, the house was for rent and Mrs. Merriam and her daughter Bertha were off for a year in Europe so Bertha could study singing.

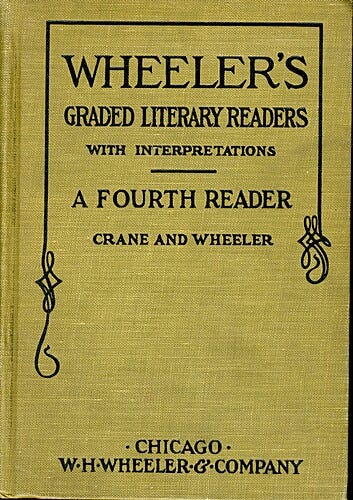

Soon after, William Henry Wheeler, founder and president of Wheeler Publishing and the author of Wheeler Literary Readers and the Wheeler primer, and his family lived there. He died in 1936. For a time, the townhouses were publishers’ row.

The El

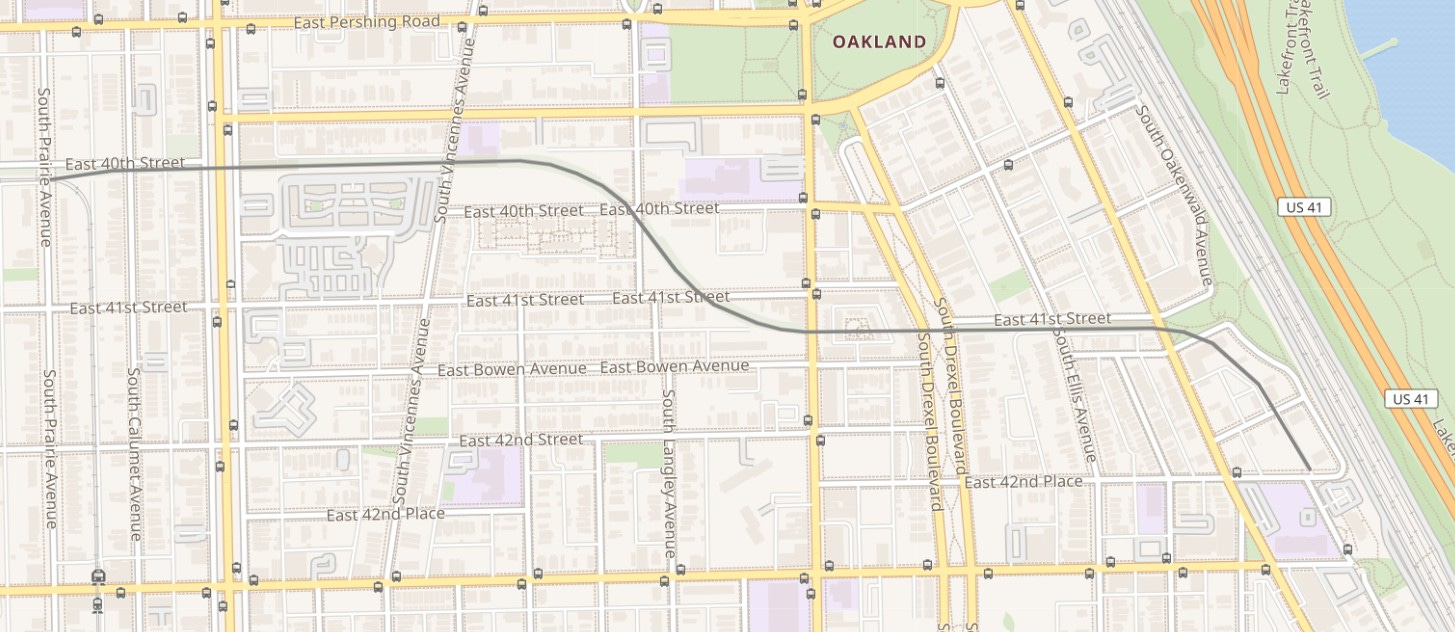

Once upon a time, there was a branch of the El system that reached through Oakenwald, north of the townhouses, to the lake, connecting the area to jobs at the stockyards and a fast path downtown, though not as fast as the Illinois Central for those with downtown offices, like Baron Volkoff. It opened in 1907, and even then NIMBYism was strong. The homeowners went up in arms and approached Williams, who, though too far south for these houses to be affected, owned investment property on the proposed route where there would be a turning ground. He promised that he hadn’t been approached and “such a proposition would be an outrage,” but the El was built.

It was closed in 1959 but remnants remain, which has inspired a new, possibly transformational project, which unfortunately may be derailed by the chaos in Washington. The proposal is to convert the right of way into the Bronzeville Trail, a connector across the South Side to the lake, that, like the 606, would transform the space.

There’s an organization trying to bring the area to life.

Another amazing rabbit hole. I truly hope the plans for the area can be realized.

Thanks, Trish, for fleshing out that photographer's tone-deaf comment on Facebook with such a thorough and interesting treatment! And thank heavens the builder's detailed description creates such a vivid picture of the original house. He was quite a salesman.