The Sons of Bitche Cross the German Border

My Father's War in Real Time

I’ve written two posts about the waiting time building up to the launch of the spring offensive on the Western Front over on the Substack devoted to just the World War II book. One was about how they could tell things were about to change because replacements showed up. The other is that Dad ended up with disorienting leave in Paris just before the offensive launched.

In mid-February, the 325th Combat Engineers and every other GI on the Western front was required to watch a short film called “Your Job in Germany.” You can find it on YouTube. It’s not subtle, though it was directed by Frank Capra and written by the future Dr. Seuss. The point the Army wanted to drive home was that the Germans are—in their essence—aggressive and untrustworthy. After all, as the film pointed out, Germany had invaded France three times in 100 years. The GIs’ job in Germany was to insure it would never happen again. Their job in Germany was to distrust every German, especially happy dancing Germans in folk costumes, because all of them—pretty frauleins, young children, old clockmakers—had supported the Third Reich. In the movie, the scenes of marching troops and Hitler Jugend intercut with dancing beer drinkers are indeed chilling as the dance of war repeats itself. The pretty woman walking down the street was walking in a dead woman’s shoes, “sent from the murder factories.”1 They were warned that the Germans had all been indoctrinated into Nazi thinking, and the entire infrastructure of society was poisoned with the Nazi toxin. The soldiers of the SS were melting into the civilian crowd. Who knew what these men would be planning.

Strategically, SHAEF kept referring back to the end of World War I, when, in 1918, the German army had collapsed and the German people rose up against the Kaiser due to hunger and exhaustion. SHAEF thought the same thing would happen. It was part of the justification for the indiscriminate bombing. But horrific civilian casualties like the fire-bombing of Dresden didn’t work. Hitler himself was obsessed with the collapse of 1918. The idea that Germany hadn’t actually lost the first war, only the will to win the war, was central to his thinking.2 He had been stripping the occupied lands of food so the Germans would not revolt in hunger as they had in 1918.

With Germany not surrendering and Eisenhower’s straight front restored, the word was out that it was time to cross the German border, fighting through the Siegfried Line of fortifications, to reach the west bank of the Rhine.

On March 7, the GIs in the 100th Division, still in their foxholes, opened up Stars and Stripes to read that others had not only reached the Rhine, they’d crossed it, using the Ludendorff Bridge, a railroad bridge that crossed the Rhine at Remagen. A lieutenant Lt. Karl H. Timmerman and his platoon had stumbled across a bridge that seemed intact. The other bridges across the Rhine were either bombed by American planes or blown up by the retreating Germans. He checked with his company commander, who said go for it. The platoon raced across it without consulting the grand strategy of SHAEF. The Germans tried to blow it up as they raced, but something misfired. Only some of the supports of the three arches were damaged. If Eisenhower had thought allowing the 7th Army to cross the Rhine below Strasbourg into the Black Forest back in November was bad strategically, Remagen was even worse. The approach was on narrow dirt roads on the west. On the east, the road ran into a 600-foot cliff of basalt before taking a sharp turn.

One theory has been that the massive charges laid at the arches had been sabotaged by the Polish slave laborers forced to lay them. Against a hail of bullets, Timmerman’s men ran across the damaged structure, holding their breath that the whole thing wouldn’t blow up beneath them. For Timmerman, it was a return of sorts to German soil. He’d been born in Frankfurt. His mother had been a German war bride of World War I.

Local field commanders threw three regiments across the shaky structure in the next 24 hours. MPs frantically directed traffic on the narrow approach roads as armored units as well as infantry edged across the planking laid on the bridge’s railroad tracks. Eisenhower’s accounts after the war made it seem as though he welcomed the improvisation. Even at the time, though, GIs knew that SHAEF didn’t welcome it. There was this anonymous poem circulating:

You know Remagen Bridge was seized

A week or two ago

The High Command was hardly pleased,

It almost wrecked the plan….

“The whole concerted war machine

Together must advance,

You dare not take an unforeseen

And accidental chance…

The 291st Engineers immediately tried to keep the Ludendorff Bridge standing with throwing a heavy pontoon bridge across the raging spring waters of the Rhine while under fire. They took heavy casualties. Between the structural damage of the initial explosion and weight of tanks going over it, the Ludendorff Bridge suddenly twisted and fell into the Rhine, killing 32 engineers and injuring dozens of others. The twisted wreck was a tourist stop for the GIs during the Occupation. Here’s Zeke Zederbaum’s photo of it.

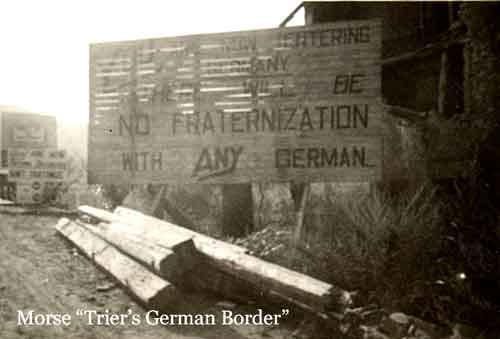

Finally, a week after reading the Stars and Stripes, the 100th Division got the orders to move out. The GIs were handed the Pocket Guide to Germany, which emphasized the nonfraternization policy. The GIs were not to go to religious services or play games or accept gifts or give candy to children or be seen talking to any German on the streets beyond giving orders. They were ordered to carry the Guide to Germany inside their helmets at all times—I guess so its statement that “Every German is a Hitler” could finally be absorbed.

On March 15, they were finally heading into Bitche. Three tanks were to accompany them but lost their treads right away to mines. The 399th had to go over Spitzberg, where the Germans had left 4,000 Schu mines and machine gun nests. The infantry tackled the machine gun nests, while the engineers cleaned out the mines and tackled the booby traps set with 500 pounds of explosives. The 399th got to the high ground above Bitche and saw that the Germans streaming downhill toward Bitche and as far as they could see, out the other side. Soon, the 399th was in a sharp intense firefight around the Camp de Bitche. The Stars and Stripes said that Bitche was taken with hardly a shot. As one of the 100th said about that, “every man has a right to his own opinion.” There were losses, including a 2nd Lieutenant who was killed in action firing a bazooka at an on-coming tank so his men could retreat. The men found it very odd that they had sat all winter for 72 days in the hills, only to get to the other side of Bitche in two days.

The 100th Infantry Division at Bitche produced one of the war’s iconic images, the photo of a GI hanging an American flag out of the second story of a hotel on a narrow street. It was used by Ken Burns to advertise his 2007 PBS series, The War. But the heroism of that photo to me is the story behind that flag.

In the months while the American army was so close, just over the hill that can be seen at the back of the photo, the people of Bitche lived in their cellars as the German Army and the SS occupied the upper floors. In the stone-arched cellar of a closed down inn, the Auberge de Strasbourg, at night, with the sound of the Germans’ feet walking on the floor over her head, a young woman named Maria Oblinger. She decided to hand stitch an American flag out of silk. It was an act that would have gotten her killed. It was her promise to herself that long winter that the Americans would finally come over the hill and liberate them. In 2004, I had the privilege of meeting her. The blue has faded a bit, the silk is delicate, and the 48 stars are arrayed a bit oddly, but it’s a most beautiful flag.

The 100th Division didn’t have long to enjoy their conquest of Bitche. They swept through town, racing toward the German border, but they left behind five 2 ½ ton trucks of food and 1,000 loaves of bread baked by the bakers of Siersthal along with a mobile soup kitchen for the citizens of Bitche who had waited for them so long.

They knew that the next stop was the Siegfried Line that marked the German West Wall on the west side of the Rhine. It had been built up along the entire border of Germany during the autumn of 1944 by foreign laborers and German women and old men conscripted for six weeks of heavy labor. The 100th Division took a day to train in the assault of fortified lines, which was worrying. Rumors started flying that Germany was a fortress.

Then the orders came to saddle up—that is, to the relief of all the enlisted men, everyone was to ride. General Burress, commander of the 100th Division, was proud that he could get the entire division onto motor vehicles. Anything with wheels became a troop transport. As Zeke Zederbaum of Company C of the 325th Combat Engineers joked on his picture of himself finally riding on the back end of a jeep, it wasn’t so bad when you could ride through the war. Crammed on trucks, clinging to the outside of tanks, and perched on the back ends of jeeps, they weren’t as comfortable as officers, but it sure was a lot better than marching.

As the others rode, the engineers were on the ground because, as the Story of the Century complained, the road was a maze of roadblocks and blown bridges.

When they got to the Siegfried Line, they were thrilled to discover that they didn’t have to carry out an assault on a fortified line. The 3rd Division had already been there. The Siegfried Line snaked to the horizon along the German border with row after row of concrete tank traps that the Germans apparently called “pimples” and the Americans called Dragon’s Teeth—punctuated with armored bunkers. Rather than explosives, Zeke Zederbaum got to wield his camera:

One of the men I talked to gave me his memoir, which described what it was like to cross the line:

The convoy rolls through the woods on a good paved road and suddenly breaks out onto a plain of rubble and dust. The fields are covered with giant pieces of concrete. A thick layer of dust blankets everything. We see only dust and debris for a hundred yards on each side of us. Our vehicles tilt and dip through the shell and bomb holes as we look in awe at pieces of concrete as big as houses torn up and thrown about. To the right and left we see the dreaded Dragon’s Teeth parading, untouched into the distance, but we drive through a gap marked by total desolation and inches deep in tan-gray dust. We smell the fumes from explosives, our faces are plastered with the acrid dust.”

The anticlimax was a relief. As the 399th Regimental History said, “I’m glad we didn’t have to fight for this baby.” They even got to spend the night in some of the dugouts and play some softball in the warm spring air. The next day, they loaded up again and rolled into Germany still on the west bank of the Rhine.

After 140 days of combat. Dad crossed the German border at 1431 hours on March 17, 1945, at a town called Schweix.