One of the things that struck me while working on Lorado Taft is how easy it is for the whims of fashion to erase a reputation. I also learned that one of the advantages of the Fountain of Time is that it won’t get lost in some basement.

A letter to the Tribune in 1966 captured what happened to the art world’s estimation of Taft—but also the public’s. The “Spirit of the Great Lakes” was taken off view while the underground parking garage was built. It was put back in a way that hid the plaque and description of the Ferguson Fund, perhaps intentionally, since the plaque makes clear that the fund was strictly for public art in parks and boulevards, not administrative wings of the Art Institute. A letter writer said he was surprised it was put back at all because it wasn’t the kind of art that the Art Institute promoted: “I figured that they would set up a fountain more like this sketch.” Said Arthur Johnson. (Tribune June 26, 1966)

Here’s where the Spirit of the Great Lakes stood originally.

The waters flow down from Lake Superior, into Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, as indeed the waters do. Lake Michigan then spills her water into the basin below, since she doesn’t flow into the other Great Lakes. Huron pours her shell into Lake Erie, who pours it into Lake Ontario, where it flows to the sea that she reaches toward. Taft admitted that he liked the way the sun arced over and highlighted the fountain on the south side of the Art Institute, but he had to sacrifice the symbolism a bit since Ontario is reaching away from the Atlantic. At least the “Spirit of the Great Lakes” is still visible, though it’s tucked into the shadows and the sun doesn’t highlight its elements as Taft had intended.

The Art Institute no longer exhibits the “The Solitude of the Soul,” which once had a place of honor. It shows how much Rodin was influencing Taft. Four figures emerge out of the stone. The marble weighs them down as much as it lets them go. They can’t quite connect. Their eyes are closed. Taft wrote, “The thought is the eternally present fact that however closely we may be thrown together by circumstances … we are unknown to each other.”

The Solitude of the Soul gives a taste of what the Fountain of Time should have looked like if Taft had found anyone willing to carve it in white Georgia marble. They had the money.

The University of Chicago also has some hidden Tafts. It once had a Lincoln Room in Harper Library with the plaster version of Lincoln the Lawyer. After all, Hyde Park was Lincoln territory, populated by close friends and colleagues. The bronze version stands in Urbana. The plaster statue is now listed as in storage by the Smart Museum.

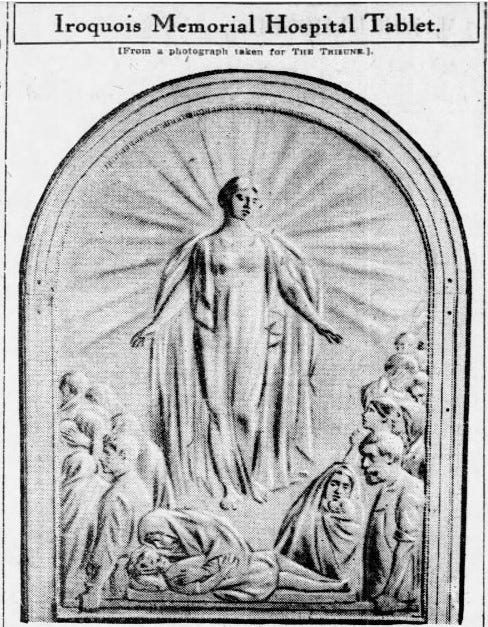

At least those statues are supposedly safe. Other works had murkier fates. In 1967, a janitor rearranging the basement of city hall came across a low relief bronze sculpture. It was almost 6 feet tall and weighed 800 pounds. It had 4 holes so it could hang on a wall. It was corroded and covered in dirt, but they thought it might have some value so they turned it over to an expert in metals. He cleaned it, exposing the signature of Lorado Taft. It was in fact the memorial to the 602 people who died in the Iroquois Theater fire of 1903. Taft was the man that people turned to when they wanted a statue to help them mourn.

The central figure is Sympathy. She’s holding out her arms to those who need it and those who give it to others. It was originally in the waiting room of Iroquois Memorial Hospital. When the hospital was torn down in 1951 for roadwork, the plaque was put into the basement of city hall and forgotten. Once it was restored in 1967, it was hung near the LaSalle Street entrance to City Hall with a plaque describing the horrific fire.

Another mystery appeared when someone stumbled across a lady with a lute, covered in dirt, in a Chicago Park District warehouse. She’d been gathering dust and cobwebs for 30 years. She’d been designed for the Lincoln Park bandshell. Someone saved her when the bandshell was torn down for road construction. After the Park District figured out what it was in 1967, they decided to put her in a plaza at Belden and Clark. The Park District even bothered to duplicate the angle that Taft had placed it in relationship to the sun.

At the lady with the lute hadn’t lost her head. One of the heads of Silas B. Cobb seems to be missing. Unlike the later plaques on campus that are still screwed onto the walls, Silas was perched over the main doors to Cobb Hall, the building he’d donated to the University of Chicago when it was just a marsh with burr oaks. In the 1930s, Silas vanished. Probably it was a frat prank. They were rather notorious for purloining startling souvenirs. Then one day, “like a foundling in a crate” according to Muriel Beadle, he reappeared on the doorstep of the university president’s house. In that telling and this University archival photo taken in 1969, he was marble and had a waistcoat.

But something dramatic has happened to Silas between 1969 and 2024. He’s lost his moustache, his waistcoat, and his marble (and needs a cleaning).

Bronze Silas looks more like his earlier photograph.

Marble Silas looks like his later photograph—moustache and all. He donated the building in 1892. This later photo dates from 1895, so closer to his appearance when he made the donation.

Taft made over 120 busts, and was famous for the quality of the portrait, though he thought it was very mechanical to just reproduce reality. Maybe Bronze Silas was an early portrait deemed by the university to be more interesting as art. I haven’t found information on when it was made or even for sure that it’s Taft’s. Marble Silas seems far more benevolent. Bronze Silas seems designed to scare the incoming freshmen.

Lorado Taft in the Herald

Just a reminder that the Herald articles do not repeat these newsletters. They are polished (not dashed off like these tend to be) and for the record.

Part I is about his active role in things Hyde Park—women’s suffrage, the 1893 world’s fair, and saving the building that now houses MSI, etc.

Part II [hopefully coming soon] is about the Fountain of Time.

For some reason Chicagoans do not seem to appreciate their cultural heritage, unlike New Yorkers. Pity.