I wrote a Herald article honoring Earl B. Dickerson because I’m convinced without his presence Hyde Park would be a very different place. The article is trimmed to focus on Dickerson’s influence on Hyde Park, but I found his life so fascinating, I had to write up all the parts I was trimming out, in a series here. I guess I’ll send one a day, not to flood your in-boxes but not to spread it out too far. Part 1 was yesterday.

Here’s the article itself:

Dickerson returned to law school upon his return to the States from World War I only to have Chicago dissolve into the race riots of 1919. The riots began when a white mob murdered a Black teen who floated too far north on the lake. Dickerson walked from the streetcars to classes carrying a service revolver under his buttoned coat. He was not going to be deterred.

His contacts during the war in France meant that Colonel Sprague invited him as the only Black representative to the meeting that organized the American Legion. Amid the riots, he formed the George L. Giles Post 87 in Chicago. In 1921, they passed anti-Klan resolutions and urged the state American Legion to pass them too. Why did they need an anti-KKK resolution in 1921? Check out the study about the Klan in Hyde Park and the South Side: The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915 - 1930, by Keneth T. Jackson.

When Emancipation Day rolled around in 1924, in spite of the Klan, Dickerson, as the commander of the Giles American Legion post, stood at the Augustus St. Gaudens statue of Lincoln in Grant Park and read the Emancipation Proclamation. Dickerson believed that Black membership in the American Legion was an important reminder of Black participation in defense of the Constitution.

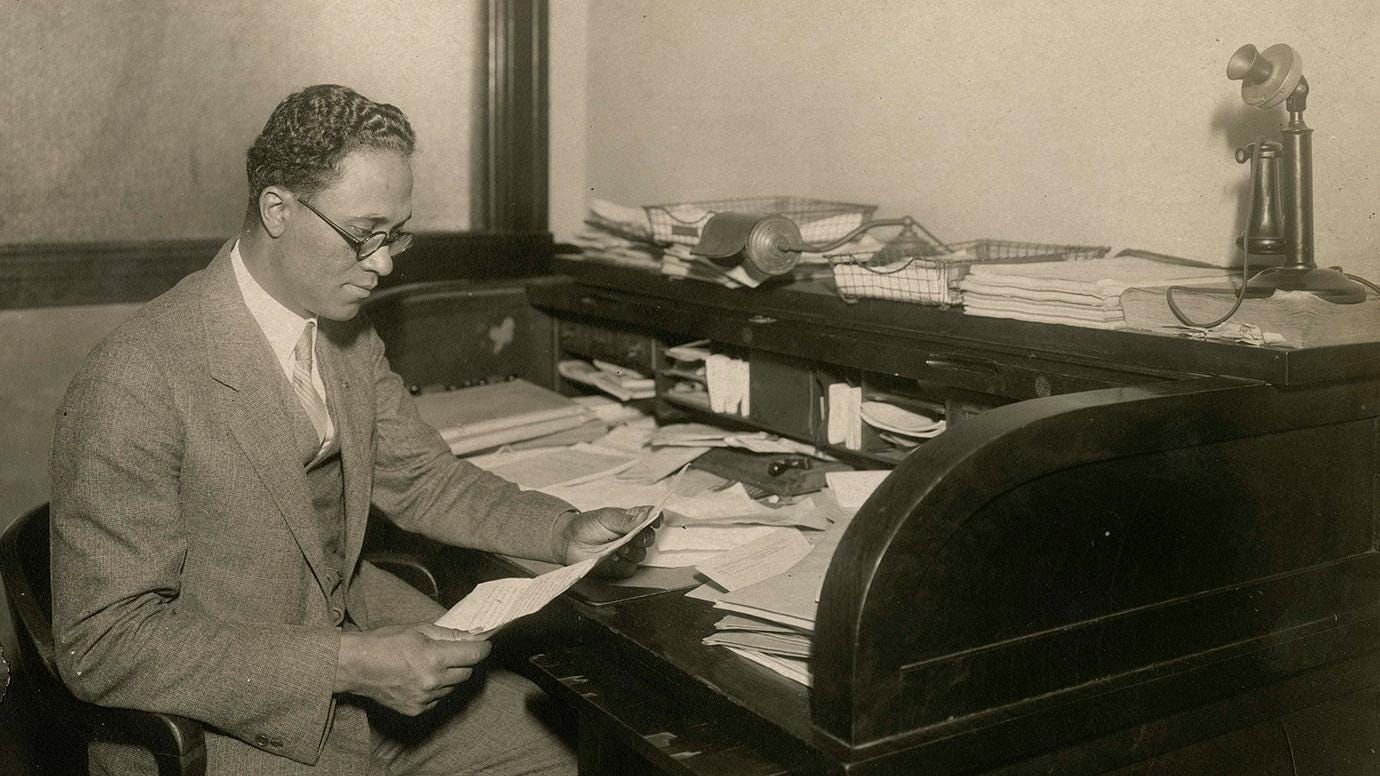

In 1920, he was the first Black student to receive a J.D. from the University of Chicago Law School. His professors said he had the best mind of any student they’d taught but their recommendations couldn’t get him hired at any major white law firm. His talents were obvious to others. In one of his first cases, he outmaneuvered Edward Morris, the opposing lawyer, in a way that so surprised him that he invited Dickerson to join his firm.

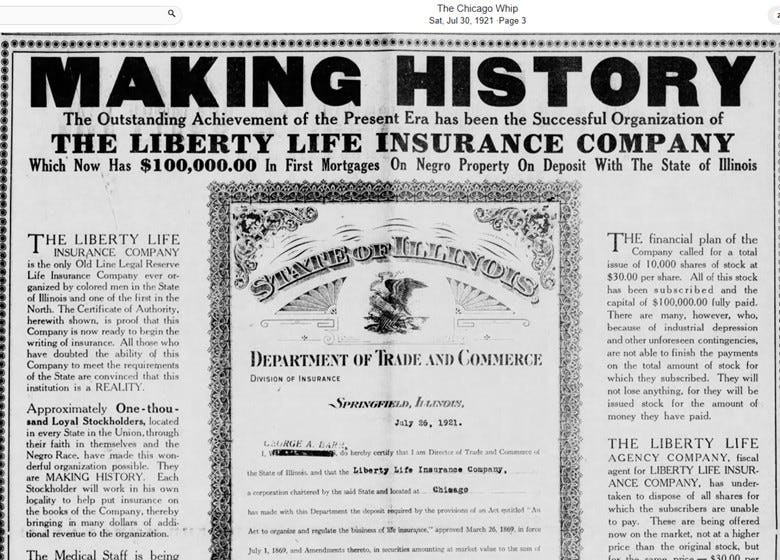

In 1920, a friend from the Army told Dickerson about a Black life insurance company that was just starting up, so he walked into Liberty Life Insurance and convinced them to take this brand-new lawyer as their counsel. Almost immediately he spotted some areas of their financial plans that would have gotten them into legal hot water. It was his expertise that eventually drove Liberty Life Insurance to become one of the wealthiest Black enterprises in the nation, known as Supreme Liberty Life.

Dickerson could have taken the advice of Booker T. Washington and simply focused on his personal economic success. It was considerable. In 1926, a short article about a car accident pointed out that Dickerson was driving a $7,000 Lincoln (inflation adjusted, that’s a $125,632 car). A 1927 article in the Black-owned Pittsburgh Courier gushed about the life of his wife Inez. She was charming, gracious, and vivacious in her white Baronette satin evening gown bedecked with crystal bugle beads, a three string pearl necklace, gold braided bracelet, and diamond rings. They admired her beautiful home at 4528 S. Parkway (aka Grand Boulevard and later King Drive). Oriental rugs graced the living room color scheme of mulberry and taupe. Her collection of antique bric-a-brac was on display near the baby grand electric reproducing piano. They did not mention that Earl and Inez were about to get a divorce.

For Dickerson, the point of Supreme Liberty Life and economic success was the change the company could achieve for the Black community. In particular, there was the desperate need for housing, mortgages, and insurance, which white firms denied. White protective associations used the 1919 riots to argue for restrictive covenants. A covenant covered a geographic area. Property owners signed onto the agreement to not sell or rent to Black residents. When a high enough percentage of the property owners in that area had signed the covenant, the covenant applied to the whole area, whether a property owner had signed or not. At the height of the 1920s and the height of Ku Klux Klan power in Chicago, the covenants also often excluded immigrants, Catholics, and Jews. If enough property owners signed on, the covenant was in effect.

During the riots, two bombs were thrown at Black-owned houses in Hyde Park near Cottage Grove. The Defender was sure that it was the protective association itself, which then blanketed the neighborhood with flyers arguing that it was better for everyone that there be complete separation. The Black population pushed back with flyers of their own and formed their own association, the Protective Circle, but many decided to retreat to safety. The Black population of Hyde Park was cut in half, though the Lake Park enclave survived. The larger problem was that the Black population of Chicago was steadily increasing as the neighborhoods that were not defined by restrictive covenants were decreasing. There just weren’t enough places to live.

From the beginning, Dickerson forged networks for resistance within the Black community. In addition to the American Legion, Dickerson also had a leadership role in the 1920s in the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity he’d helped form. He joined both the Urban League (in 1921) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, in 1920) though they were often at odds and at the time in disarray. The Urban League had closer ties to Booker T. Washington and the belief that the best way forward was economic growth and self-sufficiency. The NAACP was allied with W.E.B. DuBois’s belief that the injustices of the legal and economic system needed to be challenged. Dickerson became the chair of the NAACP Legal Redress Committee in 1926.

Dickerson traveled a lot for his many roles, and he refused to allow the de facto Jim Crow of the North go unnoticed. Illinois after all had a civil rights law. Dickerson, who was tall, very handsome, charming, and erudite, was also unrelenting and uncompromising. His first fight was with the Bismarck Hotel when three employees refused to let him enter through the front door. He sued and lost. He went to an American Legion national meeting in uniform and was refused admittance, so he sued. He protested in 1932, when Chicago made a bid to host both the Republican and the Democratic conventions by saying the tiny fraction of Black delegates could be easily accommodated in Chicago’s segregated hotels. In 1939, he sued the Abraham Lincoln Hotel in Springfield when it refused him admittance though he was on state business. He lost all these lawsuits until 1952, when his daughter and her fiancé were refused service in the Palmer House Empire Room. Dickerson sued and won. The damages were small, just enough to throw a party in the Empire Room itself. Jet magazine, however, thought it was the first victory against a national hotel chain. After that, Dickerson was often the first Black customer to be served at establishments like the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City.

Dickerson also sought to integrate the professional organizations. Refused admittance by the American Bar Association, Black attorneys could join the National Bar Association. In 1938, the Chicago Chapter of the National Lawyer’s Guild elected two Black members, one of whom was Dickerson. In 1945, he cracked the color line of the Chicago Bar Association.

In 1927, as segregation swept Chicago, it became clear that there needed to be a Black cemetery. Ellis Stewart of Supreme Liberty Life and Dickerson worked to buy 40 acres in Alsip, a white but mostly undeveloped suburb. To legally turn land into a cemetery, the owners had to bury a body before witnesses. When the routine burial party showed up, they were met by the Alsip villagers and armed police to prevent the cemetery. The burial party left until Dickerson arranged to have the Cook County deputy sheriff accompany the burial party. In the Depression, the cemetery association was about to declare bankruptcy before Dickerson arranged to have Supreme Liberty buy the mortgage and reconstitute the association. Dickerson later said that saving the cemetery was one of his great achievements as a lawyer.

In 1930, he married Kathryn Kennedy Wilson, who was much more attuned to his interests. She was a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago. They helped found the Southside Art Center, which has been critically important for launching many Black careers in the arts.

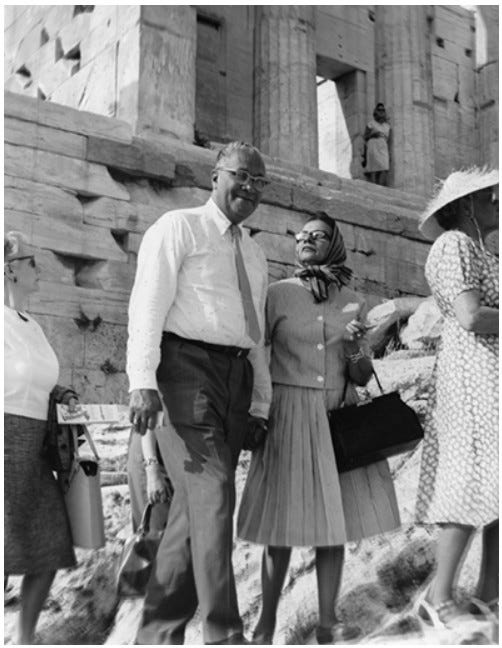

She put on fundraising galas for the Urban League and traveled the world with Earl in the 1960s.

Here’s a link to Part I:

Earl B. Dickerson Part I

I wrote a Herald article honoring Earl B. Dickerson because I’m convinced without his presence Hyde Park would be a very different place. The article is trimmed to focus on Dickerson’s influence on Hyde Park, but I found his life so fascinating, I had to write up all the parts I was trimming out, in a series here. I guess I’ll send one a day, not to fl…

This is an excellent tribute to Mr. Dickerson. I had the honor to meet him and Know him about 48 years ago. He was a kind, generous and great conversationalist.

I would visit him with Jesse Mann, someone he treated as a son when Mr. Dickerson lived in The Newport. He actually visited me in my apartment in South Shore for a holiday meal.