On November 8, the 399th regimental combat team was reassigned from the 45th Division back to the 100th Division. The other regiments, the 398th and 397th, had arrived at the front. Some rear echelon type with a grim sense of humor named the assault on the German winter line in the Vosges, Operation Dogface.

“Dogface” was a term for troops in the combat zone. It seemed to originate in the regular Army in the 1930s, but by the autumn of 1944, it had been embraced by the veterans of Anzio stacked up against the Vosges Mountains. Audie Murphy, the most decorated American soldier in World War II, memoirist, and later actor, called himself a dogface. Bill Mauldin was the poet laureate of the dogface with a hard-bitten, sardonic humor peppered with a large dose of anger. This was embraced throughout the writing of the G.I.s, both the unit histories written during the Occupation and the memoirs written down the years. It was part of the bonding between men in a unit with an angry cynicism directed at everyone else, especially the Army.

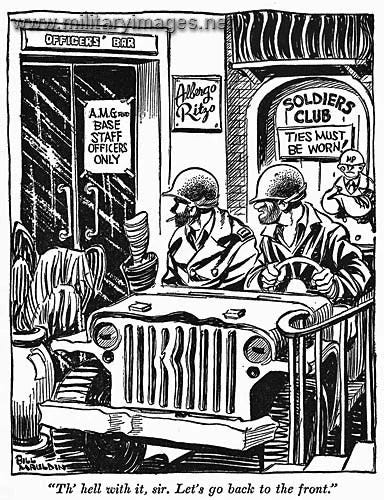

It was a badge of honor to be a dogface. Some rear echelon soldiers even mimicked the unwashed, unshaven appearance of the true dogface to gain a bit of stolen swagger, even if they were just, as the dogfaces said, Typewriter Commandos of the Chairborne Division. As Bill Mauldin pointed out, there were many millions of men inconvenienced by the Army, but it was a relative few who suffered and risked their lives in the combat zone.

Many of Mauldin’s cartoons were about the contrast between the small fraction of men in the combat zone and the rest. Supplies were difficult to deliver to the front, so there was often not enough water for drinking, let alone washing and shaving. His characters, Willie and Joe, look filthy. They slept in muddy foxholes and got covered with mud. Their clothes were torn and many layered in an attempt to keep warm. I showed one of Mauldin’s cartoons to someone unfamiliar with them, and he exclaimed, “they look like homeless people!” And so they were.

Without the water to shave with, their beards grew in. They felt that the beards kept their cheeks somewhat warmer and camouflaged white faces in the night.2 They lived below ground for days and sometimes weeks at a stretch. A good foxhole roofed over with branches and dirt was protection from all but a direct hit—but the dogfaces had to stay down. If they lit a cigarette, they had to go deep in the hole, cupping hands around the flame. Every drag on the cigarette had to be done at the bottom of the hole. The glow of the end of a cigarette could be seen from far away in the pitch dark. If dug correctly, there was room to sleep with a lower portion for water to drain, and a place to stand at the edge, where a rifle could be aimed. Unfortunately, it started to rain in November in the Vosges and it didn’t let up. It pinged on helmets. It soaked them to the skin, setting off shivering with no hope of getting warm and dry. Webbing and canvas mildewed; anything metal, including the rifles their lives depended on, rusted. When it rained, even the best designed foxhole filled with water. They’d have to sleep in the water. At least their body heat would warm the water next to their bodies, so they avoided moving for long hours so as not to lose that pocket of warmth. Sometimes the two-man hole was so full of water, the water would dangerously rise as the second man got in.

There were a few good things about the front. In the combat zone, military courtesy—all that hated saluting--and the markers of rank evaporated. The lieutenants and some of the captains were in foxholes with the enlisted men, eating cold K rations, as filthy and unshaven as anyone else. Snipers targeted anyone who seemed to be in command so most insignia was removed. They were all there just trying to get the job done and get home alive. In other words, the front meant a lot of freedom from the Army. It wasn’t just the enlisted men who appreciated that. Dad and Bagley had been drafted, done boot camp, and risen through the enlisted ranks to be sergeants before they were sent to Officer Candidate School. Dad hated the saluting. He had more in common with the men than other officers. He wasn’t alone, as Mauldin knew.

During the war, the Army surveyed the troops about the combat zone and who counted as a front-line soldier. Hardly anyone disagreed that the riflemen in the letter companies—those companies in infantry regiments with radio call names like Able for A Company, Easy for E Company, and Love for L Company—were in the combat zone. If the front meant there was nothing between you and the enemy, then the outposts were at the front. They occupied foxholes in front of the main line, scattered forward, where they could act as guards—listening and watching for Germans. Behind the outposts, was the main line of men in foxholes. It wasn’t a solid line. Rather, men in one foxhole could see the men on either side of them. That was all they could see of the war. They rarely saw even their whole unit at a time when they were on the line. These were the men who killed and were killed, up close and personal.

Fewer but still a majority of G.I.s agreed that there were others who counted as being in the combat zone especially the medics and the combat engineers. Engineers got to be behind the main line of foxholes in the reserve area some of the time, working on roads, setting up water filtration systems, leveling areas for the artillery. But then there were the other times. When I was in high school, I asked Dad whether he’d ever seen the front. He laughed and said, “sometimes we were in front of the front.”

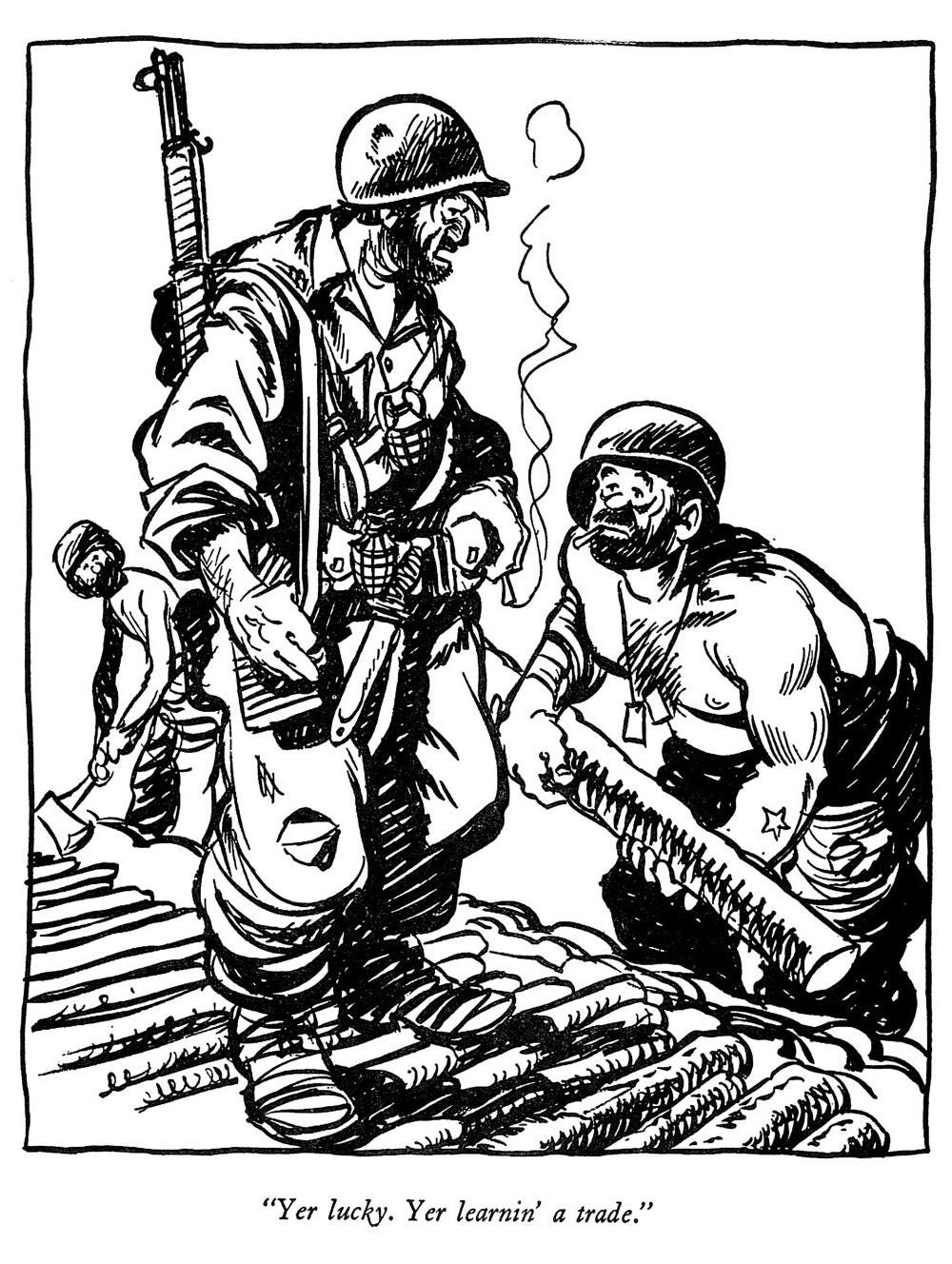

The engineers had to get in front of the front so they could build bridges in the night or clear paths through minefields—before the infantry could jump off in a skirmish line. There’s a kind of rivalry between the two—engineers and infantry. Mauldin pointed that out. There’s a cartoon of an engineer, stripped to the waist and clearly weary, standing in the muck and waiting to lower a log into a corduroy road. He stares up at an infantryman who is standing on the road looking down at him, saying, “Yer lucky. Yer learnin’ a trade.”

A couple of riflemen’s memoirs mentioned the surprise in the early days in the Vosges of coming across signs that the engineers had been there first. One soldier in the 399th recalled thinking he was on the cutting edge of the front, when they passed the body of an engineer, “lying in the middle of the road where he had been killed by an enemy mine that he was trying to disarm. His arm was reaching into the hole where the mine was buried. It exploded and it was all over for him.”Another recalled getting the order to jump off the front line and attack, only to see a lone figure zigzagging his way across an open field—it was an engineer who had set off a smoke bomb to hide their approach to a footbridge the engineers had built in the night.

A big part of their task, however, was working on the horrible French roads, which were, as one engineer said, “in no way designed for modern traffic, much less for the demands of supporting armored and mechanized armies in the attack and defense….the mass destruction of modern war made a shambles of what was already inadequate.” The engineers had to keep the roads passable to keep the men supplied with rations and ammunition while under artillery fire.

For all the miseries that anyone along the combat zone experienced from Switzerland to Belgium, there were particular miseries in the Vosges Mountains. Even the Germans felt it, though they had the advantage of defensive positions. As the log entry of the German army that opposed the Seventh Army said:

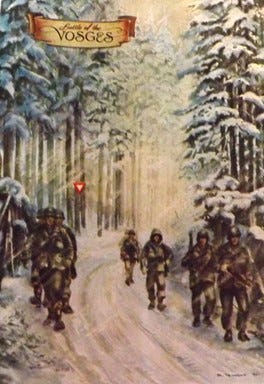

The mountainous forests have an almost jungle-like character which swallows men. The individual fighting units usually have large sectors to defend, and contact is easily lost. Also navigating through these woods is very difficult. Communications between the various fighting units and command posts are problematic….By the time a messenger reaches the command post, the situation at the front usually has already changed… The roads leading through the hilly wooded countryside have sharp drops and are bordered on the other side by steep wooded slopes. Traffic is only possible on the roads….The forests are pine and leafy trees with many thickets and fallen logs. Visibility is often no more than 50 meters. The enemy seems to appear everywhere. Because of this and the tree bursts of the enemy artillery, our soldiers do not like to fight in the forests.

The effect of the Vosges on the dogfaces was grim. Everyone comments on how the trees swallowed the light, what little light there was in the dark rainy weather. The trees were dense. Footsteps sounded loud as twigs snapped when they were on patrol. Night fell fast and early and the darkness was impenetrable. They couldn’t see each other let alone the enemy. As one dogface said

The darkness of the evening filled the forest with a dreaded stillness which was irregularly broken by those weird and nerve-wracking noises. The pine trees, swaying in the wind, whistled eerily, much as artillery shells skimming overhead. Branches fell from the aging trees and knocked against tree trunks and limbs on their way to the ground, much as spent shell fragments would batter against the trees around us. Twigs would snap and leaves would rustle on the ground, suggesting the tread of approaching feet, but more often than not it would be merely the wind playing with the forest. The night seemed to delight in playing tricks on us. Sometimes the trees, silhouetted against the skyline would dress up like humans with long bayonetlike limbs ready to strike us down. Every twig seemed to conceal a Schuh mine, every bush a sniper.

But for those used to a forest like Dad who had spent his youth rough camping in the Adirondacks, there was one remarkable fact—much of the forest floor was cleared of anything larger than a twig. The Germans had cut off coal supplies to the Alsatian towns and the people had been gleaning the brush for firewood in spite of mines.

Such powerful imagery. You are an amazing narrator!

Read today, Veteran's Day, which made it even more moving. Thank you/