Digging in for the Alsatian Winter

My Father's War in Real Time Jan 08, 2025

As Nordwind shifted to the Hagenau Forest and finally subsided in mid-January, the 7th Army took stock. It had lost 15,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. One GI who had been gone from his unit for a month with a wound, was startled when he arrived back with the 100th Division in January to see some of his old buddies looking old, lean, and haunted: “The cold predawn light reveals that my old friends have changed, and the ranks are sprinkled with new faces. Everywhere I see hollow sunken eyes, dark shadow beards, and a lethargy of fatigue from the continuous night watches.”

For the 100th Division, left out on the salient with three exposed sides, formed when all of the other divisions fell back during the furious onslaught of Nordwind, the winter seemed especially long. Where other units got rotated off the front, they were frozen in place. For the next three months, the division lived on the front, waiting for the rest of the lines to catch back up with them. The 1st, 3rd, and 9th Armies had to recover the Bulge and the rest of the 7th Army had to push back up to where the 100th Division bulged the other way. They also had to eliminate the Colmar Pocket before Eisenhower was willing to move. Since the division wasn’t allowed a respite from the front, smaller units were rotated toward the division rear for short breaks.

It was also a long terrible winter for the Alsatians just a few hundred feet away from liberation. While it wasn’t good for the Alsatian towns with the front strung in front of them, it was particularly tormenting for the towns stuck so close and yet so far away from liberation. Bitche stayed in German hands and the small devastated town of Rimling, which the 100th had held during the battle at terrible cost, was pushed back into German hands when the front line was “tidied up”. In a cellar in Bitche, a young woman decided to keep her hope alive at terrible risk to herself that winter. With the Germans occupying the rooms above, hearing their bootsteps, she found red, white, and blue silk, and stitched together an American flag. She wanted something to wave when, and she was sure it had to be when not if, the Americans finally came into town from the surrounding hills.

Dad repeatedly told me that his great dread when he was drafted was getting stuck in the trench warfare of World War I. Oddly enough, that was what the 100th Division got. Fussell who was serving nearby, confirms that it was “virtual trench warfare” that winter. For some of them, the trenches weren’t that virtual. A rifleman in the 399th team recalled:

During this time we made our holes more like home and dug connecting trenches between holes. In a day or two we had log roofs over our holes and a network of connecting trenches that would baffle the boys at Fort Benning. Each day the men would work on their holes, fixing the tops, digging them deeper until we had a line of underground huts.

As the 100th Division dug in, the engineers found themselves stringing great coils of concertina barbed wire in front of the rifle companies, which just increased the look of World War I.

Dad wrote Mom on January 11 that they had only four inches of snow on the ground. But after that the snow didn’t stop falling. It was famously one of the snowiest winters of the 20th century. The January temperatures dropped to 0 degrees Fahrenheit, and there was over three feet of snow on the ground.

The nights were so cold in January that they’d hear snaps in the night that made them jump, but it wasn’t Germans. They were the sounds of sap freezing and splitting the trees. It was so cold that if a man slept on the ground, he left patches of hair behind in the ice when he got up. And the nights were long. Dusk came around 4 p.m. and the sun didn’t return for 16 hours.

Left in place, the 100th Division felt forgotten. One of the riflemen in Dad’s combat team ended up in the hospital in early January and remembered what it was like to catch up on the news:

I read the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes but all the reports covered the First, Third, and Ninth Army actions. For the Seventh Army, the story was always the same: ‘Some patrol activity on the Seventh Army front.’ Apparently the newspaper did not think there was anything of importance to report in our part of the world. That was strange because the hospital was filled with so many of our guys and more came in every day.

There was one bit of news that heartened them, the news that the Soviets had launched a major offensive on January 12 with 180 divisions (the Western Allies had a mere 73). As the 399th official history recalled, there were ways they didn’t mind being forgotten. As GIs said to each other, “you know, I wouldn’t mind sweating out the duration and six [months] right here in this hole. We do our fighting with Zhukov and Patton via the Stars & Stripes. Nobody bothers us and we don’t bother nobody.”

One of the great things about the relatively static lines was that the men could construct deep foxholes that were also relatively dry because it was so cold. As one GI recalled, “it was one of the happiest surprises of the entire winter campaign so far, for I unexpectedly had some place to settle in and to some degree escape the cold” with his soft bed of pine branches and a sterno can burning for warmth. Roofed over with logs from fir trees and floored with pine boughs, some were large enough that they made bunks by stretching potato sacks over timber frames. Of course, the best foxholes were created by the engineers, who got to stay in one home base longer than a rifle company but who also had the equipment, the dynamite, and the know how to make them snug and large. Bob Heller, a medic in the 325th engineers Company C, recalled that they’d even wired them up to the trucks, so some of the holes had electricity.

On the front in January and February, it felt as though the earth had swallowed up all the human beings. The civilians were gone or living in cellars and the GIs were in their holes. As the intense fighting died away, the day to day fighting often became a matter of artillery booming, often in the distance, keeping a wary eye out for mines and booby traps, and occasional sharp violent firefights. One of the members of the 399th regimental combat team recalled what the night was often like:

On nights when the moon was overhead and the air was cold and cloudless, the area all around was lit with a somber grayness. At nearby foxholes, shadowy figures moved noiselessly, occasionally whispering to each other. On the ground, the snow reflected the moonlight, but the trees were gray and cast black shadows. Occasionally a white and orange flare would light the sky and the stillness would be broken by the muffled boom of a cannon seconds later. Then there would be a response from the other side—a flash and then a boom.

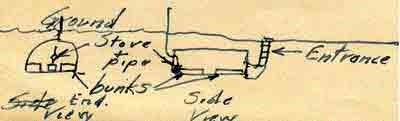

According to Dad’s letters, the officers stayed in the old Maginot Line bunkers at least some of the time. A captain in a different unit recalled that those bunkers were cold and dank. The advantage was the ability to have lights that the Germans couldn’t see for doing paperwork and studying maps at night. Dad sent home a drawing of one he was in with Bagley, Bell, and Dad’s former driver, Baumann, who had just gotten a field promotion to lieutenant and had “shiny new bars.” They had liberated a radio, so they could listen to German radio broadcasting contemporary dance music. He doesn’t mention that the price of listening to the music was listening to Axis Sally calling the 325th Combat Engineers “the Underpaid Butchers of Bitche,” making it clear that they had a target on their backs. The division itself was called out at the Terrible Hundredth.

The GIs all deeply appreciated the little things: a warm spot, a good sleep, and moments of stillness. One of the men of the 399th recalled what it was like to gaze up at the stars in the crisp cold January night:

I vividly remember looking up at the sky at night from my foxhole and seeing the most beautiful panorama I had ever seen. The sky was filled with billions of stars against a clear black background, not a cloud anywhere, and it was cold. There was no moon, only shooting stars, a shower of meteors, streaking down from every direction. The Milky Way never more brightly lit and I was like a little mole looking up from a hole in the earth.

As always, you make the war real. Human beings trying to survive in the worst of conditions, but able to still see wonderment in the world.

Harrowing but beautiful, in a way. Thanks as akways!