Sorry about the double post, but I have to catch up with the real time of Dad’s war. Footnotes are over on the other substack. Enough folks here are interested that I’ll keep posting most of the war here—but remember that you can always make it so you only see Hyde Park/Chicago posts.—

For the 399th Regimental Combat team, there was a lull in the action while they prepared defenses. By December 20, the 100th Division line was spread very thin across the Third Army and Seventh Army fronts. The 397th Regiment was around Rimling, a junction of roads on the west. Dad’s battalion team in the 399th Regiment was spread out east of Lemberg.

The lull was welcome. For one thing, some, but not all of them were issued winter gear. A particular prize was a parka that was white on one side for camouflage in the snow and fur lined. The weather December 21 and 22 was extremely cold, so cold no one could sleep in the fox holes.

The men had time to write home. On December 17, Dad wrote Mom, though the sense of the distance growing between them crept in:

The days are tough but manage to get good sleeping quarters. I wonder if the safe sane life wil ever be mine. I can't picture myself spending an evening home with you knitting--a monotonous picture. Saverne is a pretty little town--Made a bargain for apple pie.

The lull also meant they got letters, packages, newspapers, and magazines from home and the sense of distance intensified. If the news was cheerful and supportive, the men were all too aware of what they were missing and increased the homesickness and longing of young men. Too often though the news from home brought the realization that no one there had a clue what they were going through and that support for the war effort was dropping. The most obvious blow came of course from the many “Dear John” letters from girlfriends breaking up or wives asking for a divorce. The Red Cross estimated that the 7th Army alone got five letters a day announcing a divorce.

More universal was the news that the folks back home were sure the war was just about over. The newspapers were full of people protesting that they were no longer willing to make concessions for the war effort. It was inconvenient and tiresome and no longer seemed necessary. In Chicago, nightclubs were taking reservations for victory celebrations. It wasn’t just the civilians. The Office of War Information had Frank Capra make the propaganda film “Two Down and One to Go” about the surrender of Italy and Germany in 1944, they were so sure the end was near. As early as August 1944, Life was reporting that war workers were quitting their jobs to get civilian jobs to beat out the returning soldiers. The soldiers' anxiety about a return to a competitive disadvantage—if they could return in one piece at all—was intense.

By 1944, people were thoroughly tired of rationing and “Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without.” They had money in their pockets and wanted to spend it. Some luxuries, whiskey, for instance, disappeared in 1944. The distillers had been switched to war production and the reserves had run out. Canned beer disappeared because there was no tin for cans and cigarettes started to become scarce in 1944 because the tobacco crop had been smaller than usual, which was in part due to bad weather but might in part be due to the farm worker shortage. What cigarettes there were, were going to the military. In Delaware County, the nice brands of cigarettes had been scarce for a couple of years, but in November 1944 all cigarettes became scarce. The local paper advised people to roll their own.

The Christmas packages that the men received had been sent in October. The news was out of sync. By the time Christmas rolled around in the States, the mood had shifted. News of the Battle of the Bulge was frightening and chaotic. At home, that Christmas season, the stores were closed at dusk in the northeast because the use of neon and excess electricity was banned. This wasn’t civil defense. This was the severe shortage of fuel in the bitter winter weather. It sunk in that the war wasn’t in fact over.

There was one thing that everyone was sure of. There was someone they were missing. The best-selling song of the war for two years running was Bing Crosby’s signature song, “White Christmas.” It’s a song about the longing to be elsewhere, steeped in nostalgia and longing for the Christmases “just like the ones I used to know.” The war also brought a second hit Christmas song that promised “I’ll be home for Christmas,” which concludes the singer would be home “if only in my dreams.”

Dug in around Lemberg, reading their letters and newspapers from home written in October, the men of the 100th Division knew home was far away. As one of them recalled Christmas,

in 1944, I was with my platoon, somewhere in the eastern part of France. It might as well have been somewhere in the eastern part of the moon as far as we were concerned. We didn’t really know, nor care much, where we were. We just wished it was somewhere else.

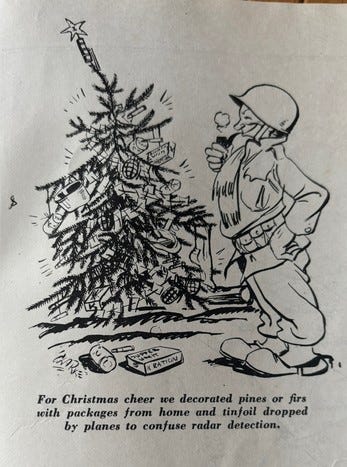

Some men set up little pine trees and decorated them with flak, silvery strips of tinfoil dropped from aircraft to confuse radar. Some joked that grenades looked like ornaments.

The best Christmas present was just to have a warm dry place for the night, some candies and crackers and sardines from home, and a bath.

For many, the Christmas lull meant lining up something to drink. The officers got an alcohol ration, but the enlisted men didn’t—yet another grievance toward officers and yet another way the home front exhibited its cluelessness about the war. The temperance movement back home had insisted on nothing stronger than weak beer for enlisted men.

Many of the men that Christmas reported that they were looking for schnapps. I was thinking that was something like peppermint schnapps until I went to a reception in a tiny Alsatian town during the 2009 battlefront tour with the Nisei veterans. There one of the French re-enactors devoted to the GIs of the 36th Division brought out a bottle of his homemade schnapps. It was as crystal clear as water and was the most intensely alcoholic substance I’ve ever been near. I don’t even know what it tasted like. I just know it made my eyes spin from just one tiny sip. When I asked what he’d made it from, he said “wild blueberries.” If that’s what the guys were getting when they were trading for schnapps, they were feeling no pain.

The GIs shared their Christmas packages from home as they could. One of the men of the 399th recalled a particularly good one:

It seemed apparently to be a good time for a mail delivery, which, given the time of year, was heavy with Christmas packages. There were of course many of the usual totally impractical gifts from loving families, like bedroom slippers, pajamas, toilet articles, and other things of no use if you lived most of the time in a hole in the ground. There were the usual highly anticipated boxes of cookies and candy and other goodies that we always looked forward to and appreciated so much. For me also was a kind of mysterious, quite large package from my mother. When I opened it and found inside two No. 2 juice cans, I began to slowly realize what it could be. My mother had somewhere read about the possibility of mailing alcoholic beverages to soldiers overseas—a practice most stringently prohibited and discouraged—by inserting the bottle in a loaf of soft white bread and then stuffing the whole mess inside a juice can. Alas the first can yielded a little pile of glass fragments and an odd colored mess….but victory was mine when I found inside the bread of the second can a half pint bottle of Wilson’s That’s All, an inexpensive blended whiskey of the time. We all “knew” that the good stuff went to the officers’ clubs in those days so it wasn’t a disappointment. Far from it. It seemed more like a miracle. I took the first long satisfying drink and passed the bottle to the squad members eagerly gathered around. I don’t know how many actually got some, but the bottle was empty when it got back to me, and a few miserable filthy unhappy GIs felt for a few moments the unmistakable spirit of Christmas in the most unlikely place for it imaginable.

On Christmas Day the mess sergeants made an extra effort to get a turkey dinner out to the troops. It arrived ice cold in the far forward outposts after dark, but for those like the engineers who were closer in, the food tasted swell, or so Dad told Mom:

Dearest

I had a very nice Xmas—turkey and all the fixings even a fifth of good old poison. Back in my nice apartment with the twin beds which added to my Yule cheer.

We have had some beautiful clear days, not much snow as yet. Waiting for some snow to track these deer over the mountains.

Received the pipe, thanks—get plenty of tobacco and matches all the time. Not always my brand of course.

The Mercedes-Benz is going strong. Think I will bring it back for a souvenir.

Love

Gordon

The holiday didn’t stop the regular rounds. Christmas Eve was marked by Company C working on a roadblock on the Bitche-Freudenberg Road at Fort Schiesseck to block a possible tank attack rising out of Bitche. As usual, the riflemen liked to laugh at the engineers, who took off when a German patrol started shooting. The German patrol was routed by a squad led by an 18-year-old staff sergeant who’d inherited the rank after the others above him became casualties.

On Christmas Day there was an especially great gift to the 325th Engineers, no casualties.

What a gift, indeed. No casualties in the midst of hell.