This is the story of how Chicago might have had its own Arc de Triomphe. In the 1890s, after the World’s Fair, there was a lot of effort going into memorializing the Civil War and through monuments defining and redefining what the war had meant.

The veterans of the Union Army, who had fought so that the “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth” shared a brutal experience that no one but themselves could understand. So they formed the Grand Army of the Republic, which was part fraternal order (when fraternal orders were essential social glue) and part the lobbying organization for veterans’ issues. Every year they would gather in national “encampments.” Chicago had been a hot bed of Lincoln support and abolitionist fervor, so the GAR was a local force to be reckoned with.

However, with time, there were economic incentives to pursue “reconciliation” with the South, where the wealthy were reasserting white supremacy. By the 1890s, there was the Confederate Monument in Oak Woods Cemetery, which reframed the prisoners of war buried there as the Lost Cause. A local chapter of the GAR erected the statue of Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address nearby in rebuke.

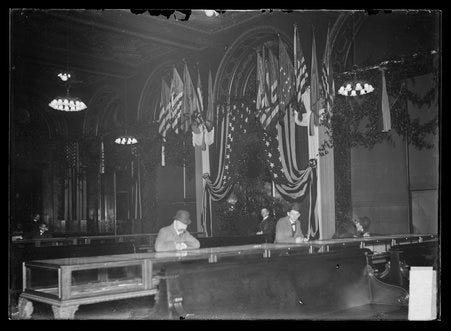

The men who fought to preserve the ideals articulated in the address felt the need for more. They owned land along Michigan Avenue where they wanted to erect a meeting house and exhibit space. When the city of Chicago decided that’s where the public library should go, they surrendered the land in exchange for a large meeting room filled with displays celebrating the accomplishments of the Union soldiers of Illinois. Two years after the Confederate Monument, the GAR had their room in what is now known as the Cultural Center.

The space was designed by Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge; the 62,000 piece dome is by Tiffany. The 2022 restoration is gorgeous.

The artifacts that used to be in display cases throughout the room are mostly in the Harold Washington Library archives, but the chandeliers, the windows, and green marble have been recreated.

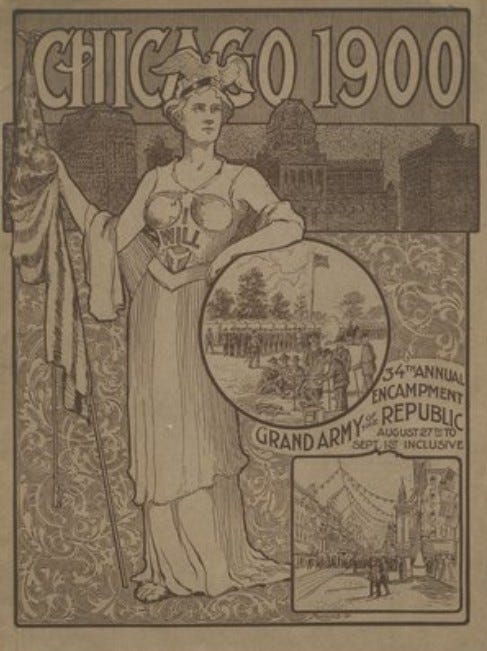

In 1900, the GAR annual encampment was once more scheduled to be in Chicago, and they decided to make it a spectacular affair with the gorgeous rooms to show off and the victory of the Spanish-American War to celebrate.

They predicted that 100,000 members of the GAR would gather. Over a million people attended the parade to see Admiral Dewey and President McKinley. Also in attendance was William Jennings Bryand and the Duke and Duchess of d’Arcos, somewhat oddly representing Spain at the celebration of its defeat.

It was a great return to the city that 7 years before had hosted the World’s Fair where its mascot Miss I Will had been born.

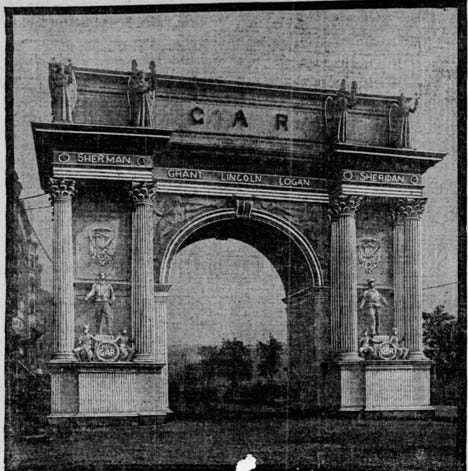

And Chicago was going to put on a show. The parade route started at Michigan and Randolph, west to State, then circled around the Loop, before heading east on Jackson to Michigan, where they marched south to about 12th Street, past the viewing stand. The long stretch of Michigan was redubbed the Avenue of Fame. On the north was the massive arch of the GAR itself. On the south was an arch dedicated to the Navy in honor of Admiral Dewey. In between were 132 pylons, each topped with a globe. The pylons were 300 feet high and displayed shields with the Chicago Y, the municipal device. The pylons each had 13 electric lamps outlining the shields. The arches themselves were illuminated.

The GAR arch displayed the names of Sherman, Sheridan, Lincoln, Logan, Washington, and Grant. The arch had eight statues of Peace, statue groups representing infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineers, signal corps, and hospital corps, and right over the arch winged Victories with trumpets. The statues were done by Richard Bock (one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s collaborators). Over 28,000 people marched through the arches. The parade lasted four and a half hours.

After the parade, dignitaries and aged veterans gathered in their new spectacular hall under the Tiffany dome. And that evening, they viewed a pyrotechnical spectacle recreating the Battle of Santiago in the undeveloped land east of Michigan Avenue. This wasn’t the most amazing spectacle, however. I think that had to go to the sham battle held earlier in Washington Park by the 1st and 2nd regiments of the Illinois National Guard, 1st Illinois cavalry, and the US artillery unit from Fort Sheridan. In front of 100,000 spectators, 1500 soldiers fired off 60,000 rounds of ammunition.

The ranks of the GAR were so moved and Chicago itself was so proud that there was an immediate campaign to recreate the GAR arch in marble as a permanent memorial. It was proposed to make it even larger—80 feet tall—and place it somewhere where all could see it—but where?

It would be grand on the Midway Plaisance at Woodlawn where the Ferris Wheel once stood. It would shine down the long vista. And there was less of the hideous coal smoke that blackened everything downtown.

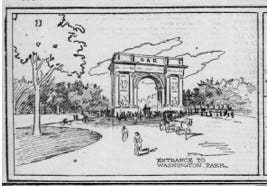

At Washington Park, where the battle had been held, it could be a grand entrance off Grand Boulevard (now King Drive) into the gorgeously landscaped grounds with the famous rose garden and immense conservatory.

But the most popular idea was to make it the entrance to Lake Front Park if it ever got out of the planning stage.

One of the main issues with Lake Front Park was how to connect the east side of Michigan Avenue to new landfill west of the Illinois Central tracks and make it inviting. They proposed that the arch could provide the proper vista as it led to a monumental viaduct near where Balbo is now. On the other side of the tracks, the new Field Columbian Museum would be on the north and a monumental exposition building would be on the south. Directly east would be a stunning fountain, visible through the arch to lead people into the park.

Of course, the Lake Front Park took decades to manifest as Grant Park. By then the veterans of the Civil War were very old men. The problem in putting it elsewhere, as with most plans, had turned out to be money. Many offered to give money but only if it was in their favorite park, Garfield Park, or Lincoln Park.

The idea faded away and the veterans made do with their beautiful meeting rooms and hoped succeeding generations would remember the sacrifice they had made defending the Constitution.

So glad to know this history! Thank you again!