I’ve gone back to Substack. Social media raises all kinds of ethical issues for a free service, but they all do. I am reassured that there are many accounts I admire that remain. The problem is that the alternatives are designed for big profitable accounts. I’m just a little account trying to do this for free. I’ve had problems trying to fit with Beehiiv. The trigger to change now is that I stumbled into the fact that Substack solves my dilemma. I know I have followers interested in Hyde Park specifically. Others will be interested in my work on 20th Century America and World War II/family history. Some will be interested in both. I can label things in Beehiiv but I can’t stop everything from going to everybody. Then I discovered that Substack allows sections. And you can choose which sections to get.

If you go to Manage My Subscription by clicking on your profile, you can choose what you hear about. The Things They Left Unsaid is the working title of my World War II/family book. Sorry about the confusion. Some days I think I’m getting too old for the internet!

Explanation: The newsletters do not duplicate the Herald articles

I’ve been assuming all along that that was clear, but I’ve been told some people don’t bother to click through to the Herald. The content is different and the writing is way better since I have to fight to reduce my word count. The narrative is sharp and focused. The newsletters are me muttering about the process or sharing things I can’t use in the Herald for various reasons. For those who have missed all the Herald articles, I’m listing them here if you want to check out something you’ve missed:

https://patricia-morse.com/hyde-park-stories/

By the way, I am slowly consolidating old posts from all the various places into my website blog, which you can subscribe to.

And now, murals

I’m working on a Herald article about William “Bill” Walker and the radical mural movement as it intersected Hyde Park. I’ve been digging hard trying to find images of the murals that have disappeared. Unfortunately, most of the images I’ve found don’t have clear permissions or even sources. Or the quality is poor. But I can share them here because if anyone says it’s not fair use, I can readily take them down.

The murals under the viaducts have short lives because of exposure and because there was a graffiti vigilante who covered up tags with squares of white paint. I’m saddest about the loss of the Spirit of Hyde Park by Astrid Fuller because it had such a big impact and reminded us of the history of segregation, urban renewal, and the hard effort to integrate.

Here’s a panel that still exists but the clarity of the background that shows the bulldozer is clearly a comment on urban renewal is hard to see.

The narrative runs from west to east, from segregation, with wealthy white people behind the metaphorical wall of the restrictive covenants to integrated families enjoying the lakefront together. Oddly, it’s the early struggle that remains. Most of the transition and the peaceful finale are gone. This is a passage totally lost where Black and White together fight to prevent the expressway from going through Jackson Park.

And here is what wrapped around the eastern end—children playing on the lakefront, with two small families in the foreground. The families were redone but the lakefront vision is gone as are the wonderful architectural details painted into the mural that tie it into the viaduct’s stonework. The family on the right is now a lesbian couple.

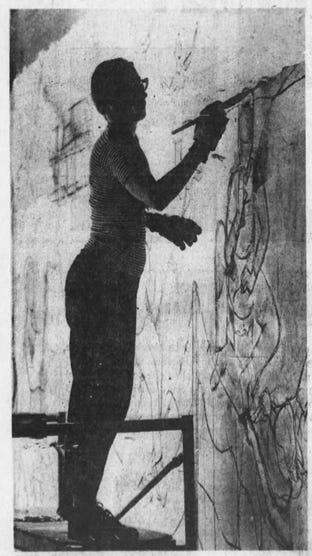

Here’s Astrid Fuller in action. The 5th Ward Democratic Committeeman got the city to steam clean the 207.5-foot, 10 foot tall wall, wire brush it, and cover it in white primer. Fuller then chalked in a grid of one-foot squares to transfer her design, which she sketched in with charcoal.

When the Metra station was redone, a new section opened up, so they added panel from her long gone mural “Women’s Struggle.” It’s a social worker freeing children from a sweatshop. Unfortunately, a fire in that corner destroyed this panel so this is the only look at it I found.

The politicized mural movement began with William “Bill” Walker and the Wall of Respect and a lot of other Black artists. The wall celebrated Black heroes, which was still radical in 1967. It launched a national mural movement, as documented in Jeff Huebner’s Walls of Prophecy and Protest: William Walker and the Roots of a Revolutionary Public Art Movement (2020, Northwestern University Press).

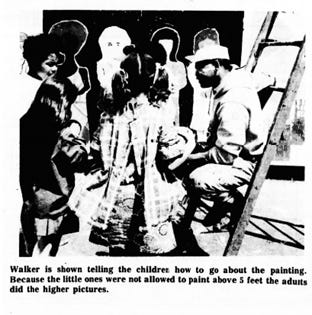

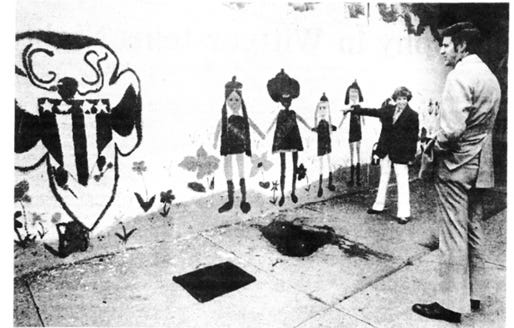

While Hyde Park’s muralists—Fuller, Yasko, and Zeno—were inspired by Walker, he himself did only three projects. After his daughter’s class at Murray went to see the famous Wall of Respect, they wanted to do their own wall, so he helped the children cover a building called the Cottage, devoted to arts and nature study, with a mural called Wall of Unity. Here’s Bill Walker himself in 1971 helping the children.

This inspired a whole wave of murals by children. My favorite was the Girl Scouts mural on 56th Street that I’d walk by every day. It’s been whitewashed away.

Walker was criticized for working with white artists and for working on a vision of racial harmony, but some of his art was very much about Black civil rights. One of them was “Justice Speaks: Delbert Tibbs/New Trial or Freedom” on the northwest side of 57th Street. Tibbs, a Black seminary student from Chicago, was hitchhiking through Florida when he was arrested and wrongly convicted of rape and murder. After a long legal fight, he was released from death row. Tibbs himself came to the dedication. This is the only image of it I could find. The Metra station built space for a coffee shop, now empty, where the mural was.

On the South Side of 55th Street, now mostly covered by the vinyl art panels, there was a mural that was once called the Wall for the Atomic Age then got reframed for local environmental disasters as Alewives and Mercury Fish. I read about how pretty the explosion was and finally found it. I’m sorry the bicyclist and the drummer are gone too. The first pyramid, now gone, showed the possibility of living in harmony with the sun and stars/planets.

This is Albert Zeno himself, taken in 1972

.