Dad and the men of the 100th Division, never knew that they had stopped outside Strasbourg because Eisenhower refused a tactical strike across the Rhine. They all had a theory that it had something to do with the French. It was just as well that they didn’t know that the German command thought the “Western Miracle” meant that the Americans were simply “too bloated” to finish the job. They believed that, with a few swift blows, the Americans wouldn’t have the stomach to go on.

The military historians who had stumbled into the realization of what happened at Strasbourg were compelled to point out that what Eisenhower ordered next was not what military tacticians would call a sound strategy. Military strategy is apparently all about the concentration of force, but Eisenhower ordered General Devers to divide his forces and spread them thinly in several directions, separated by rough terrain, which would mean one group couldn’t support the others. Some of the Seventh Army would recross the mountains and point north, next to Patton’s Third Army that was still stalled outside Metz. Much of the rest of the Seventh Army would stay on the east side of the mountains, facing northeast, east, and even south, toward the Colmar Pocket.

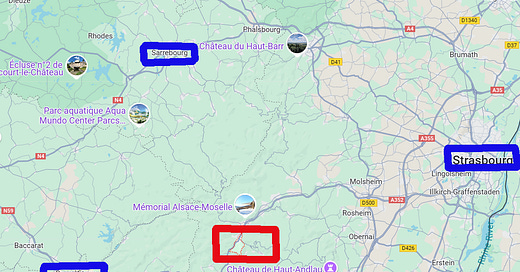

On November 25, Company C of the 325th Combat Engineers had come to a halt in the town of Rothau. They had no idea that Rothau had been a railroad transit point for prisoners being shipped to Natzweiler-Struthof, the French outpost of the Holocaust in the nearby mountains. The inmates of the main camp at Natzweiler-Struthof had, for the most part, been resisters and political enemies of the Reich from a wide range of occupied countries, but the starvation, the gas chamber, the crematorium, the “medical research” labs, the slave labor, and the watchtowers, these were all there. Many German companies exploited the labor in it and the surrounding network of camps. The SS itself had a company—the Deutsche Erd und Steinwerke—that made money by quarrying a vein of pink granite found only in the Vosges that was in high demand by Hitler’s architect. The average time of survival in the quarry was six months. Many of the inmates were French maquis, seized by their own government for resisting the Germans. When U.S. military intelligence entered the camp, they found that it had been swept clean of inmates and records, though it was clear what had happened there. And yet, in November 1944, for whatever reason, the discovery of the camp was not publicized. The first mentions crept into the U.S. news in January 1945 when a few journalists bumped into survivors who told of unbelievable horrors. The stories are brief short columns buried in back pages. It wasn’t until France started reckoning with its past, decades after the war, that the camp took its place in history. It’s another part of the silence that surrounded the Seventh Army.

On November 28, the 100th Division learned that it was assigned to the corps on the west side of the mountains. They were joining three other divisions pointing north into the Low Vosges toward the strongest fortifications of the Maginot Line and the Siegfried Line. General Patch, commander of the Seventh Army, assigned the 100th Division to the section with the most hills, the deepest cut valleys, the densest forests, and several of the largest Maginot forts. My first reaction was that that was horrible luck, until I found out that Patch and his headquarters had put the 100th Division there because it was the unit that they thought could most easily keep pace with the others who were moving through easier terrain. It was the horrible luck of being thought capable.

As soon as the 100th Division was reassigned to the group on the west side of the Vosges, the other two regiments moved by motor and foot back over the terrain they’d captured. The 399th regimental team entered reserve for a few days. While awaiting orders, Company C of the Combat Engineers spent the time clearing mines, cleaning equipment, and building facilities for the medical corps. Letters from home caught up with the men.

The letters from home had to feel both welcome and disorienting. Mom tried to write every day, but days don’t offer a lot to talk about when going through the rounds of teaching in rural upstate New York. Maybe she mentioned that Elmer Beach of Sidney Center was proud to have voted in his 16th straight Presidential election. Maybe Mom mentioned that her students were having yet another paper drive. She probably didn’t tell him that women were losing interest in volunteering at the Sidney Red Cross and rolling surgical dressings because people thought the war was winding down. Maybe she mentioned that his Aunt Dorothy and Uncle Hugh had driven up to Elsmere to visit his folks and his brother Ray. It had to seem so far away. In the few letters he did send from combat Dad had little to say about her letters. The difference in experience created a silence.

On December 1, General Burress, commander of the 100th Division, came to inspect the 399th regimental team, including Dad’s engineers. Apparently they passed inspection because on December 2 they followed the other two regiments west across the Vosges.

[If you want just the war, you can subscribe to my other substack, link below. That one has the footnotes and a bibliography in the pinned post.]]

Thanks for this look at the war. I only experienced it indirectly as a child in Des Moines, Iowa -- two of my uncles enlisted, but not my father or anyone in my immediate family in later wars.