"A wild west opera combined with Al Capone"

My Father's War in Real Time

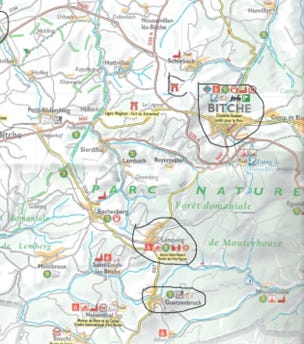

Having gone back over the Vosges Mountains, the 399th combat team headed north. Its destination was the Maginot Line forts around Bitche, which guarded the pass toward Germany. Their path passed through Goetzenbruck and the crossroads town of Lemberg.

December 4,1944, seemed relatively uneventful—Dad’s platoon built a timber bridge to replace the one the German’s had blown up, and they continued to clear mines along the road to the small town of Goetzenbruck.

The men never knew that December 4 was also a fateful day for the Century Division for other reasons. It was the day when the head of Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, decided to renew the fire bombing of German cities. That night, British bombers, finding their primary targets obscured, dropped two thousand tons of incendiary bombs on the German city of Heilbronn. A British prisoner of war in a camp near Heilbronn reported that the bombers

came circling over, wave upon wave, black shadows gliding across the floodlit ceiling, releasing their hissing bombs and slowly veering away. The flames were replenished from time to time and the countryside for miles around was flooded with yellow light.

During the Heilbronn firestorm, 7,147 German civilians were killed.

In 2004, on the battlefield tour, we saw the story of the bombing in three dioramas—the city before the bombing, the city after the bombing, and the city now. After the bombing, with only the church standing and the rest of the city in rubble, the rubble was pushed into the river, changing the course of the river. After the guide explained that thousands had died in that raid, a raid that achieved nothing militarily except to stiffen their determination to fight to the bitter end, Bob Heller, medic for my Dad's company, looked at me and said in a stricken voice, “Heilbronn smelled of death.” All the bombing did was set the stage for a bitter futile battle late in the war.

Luckily, the men didn’t know what awaited them. On December 5, in a heavy snowstorm, the 399th took Goetzenbruck. One of the battalions moved to support the 398th at Wingen. The engineers maintained the bridge between Wingen and Goetzenbruck and checked for mines in the culverts. In the process, Company C suffered two casualties from shrapnel—T/5 George Rebele and Pvt. John Dahlia.

As the infantry letter companies moved forward, the engineers set up a bivouac in Goetzenbruck on December 6.

On the 2004 Battlefield Tour, we had spent the day in Wingen learning about the 398th’s battle there (and the Nordwind battle later) and were on our way back to the hotel in Bitche, when the veteran with us from the combat engineers, Bob Heller, called out, “stop the bus, stop! This is Goetzenbruck.” There were five of us on the tour representing the 325th engineers, so we held a bit of sway. We got out and walked around for a few minutes for the unscheduled break. Bob Heller spotted the house where he’d been bivouacked.

When Bob found the church, a memory hit him. He recalled that the villagers had come out from their cellars to greet them. As in most of the Alsatian towns, the villagers consisted of women, children, and old men. Just as they were all gathered in the square, the Germans, as the history of the 399th puts it, “sent long whining salvoes of 88’s tearing over the high ground into Goetzenbruck.” What Bob Heller had remembered was the sight of a young boy, just four years younger than the youngest GIs, killed by the shrapnel. It wasn’t the moment he was hit that struck Bob. It was the memory of his brother carrying the broken body away from the church. It was a sight that effected others in the 3rd platoon. Another veteran had written to me about the sight in Goetzenbruck.

I had to laugh that Bob also remembered exactly where the all-important mess for Company C was though it was only there two days. Dad was still officer of the mess. It remained his duty, working with the God-damned cooks, even with everything else going on. Officially, the GIs weren’t allowed to consume local food. But barter was universal among the mess sergeants and supply sergeants. One of the men on the battlefield tour who had been a supply sergeant recalled that as soon as they were in a town, he’d take flour from the American supplies and find a bakery. In exchange for an extra sack of flour, he’d provide fresh bread for the men in his unit. Then in one town near the German border, he hit a baker who wouldn’t cut a deal. He learned later from another villager that the baker was a Nazi sympathizer.

There were mixed loyalties in Alsace/Lorraine. On December 3, the third platoon of Company C of the 325th Combat Engineers had one sentence and one sentence only in their morning reports: “Civilians in the area are not to be trusted.” Sixty years later, an author, John Gimlette, toured through Alsace, retracing the 100th Division. On his travels he spoke with an elderly Alsatian farm woman. She blamed the Germans for taking her father off to the Eastern Front, blamed the French for being no help, and blamed the Americans for bombing her town to bits. He asked her who had she wanted to win during the war: “What did we care?” she snorted.

What the Americans didn’t know was the damage that five years of German occupation had done. As a fascinating book called The Taste of War spells out, Germany had “exported its wartime hunger to the occupied lands.” I had known that the Germans had taken the young men and sent them to the Eastern Front, but they had also taken agricultural workers to work on German farms. Across France, 400,000 farm workers were gone. As the Germans pulled back, they stripped anything that anyone—French or American—could use.

Some of the citizens of Alsace may have been lukewarm because they felt a lack of confidence that the Germans were gone for good. It wouldn’t pay to be known to be welcoming the Americans if the Germans returned and retaliated.

Part of the lack of enthusiasm may have been that the American soldiers were bivouacking in their houses. In France, the people could stay in their houses, but they had to share. In some cases, it worked out well. As one young soldier in the 399th wrote home, he was billeted with a family where he practiced his German and brought them G.I. rations so they could combine their resources of food and wine for meals together, “People seem glad to have us.”5

For others, not so much. Particularly for the 100th Division, where many men came from New York City and New Jersey, the rural life was incomprehensible. They felt little empathy for subsistence farmers who kept their animals on the first floor of their houses, including the great piles of manure, for the heat it generated. There wasn’t always a lot of empathy. To many of the G.I.s, the civilians were “simply another feature of a foreign, strange, and frequently bizarre world.”6

On December 7, that “gray and rainy anniversary of Pearl Harbor,” the engineers cleared mines on the road out of Goetzenbruck and cleared large abatis until they were driven off by in-coming mortar rounds. In their dry warm bivouacs, they were able to write some letters home and for once, Dad wrote to Mom. His letters were extremely infrequent. In addition to the silence that was becoming a central part of his character, he had the common problem for the lieutenants. He had to do what his platoon was doing and then when they rested, he had to travel to the command post to get the instructions for the coming day. He often just fell asleep on the hood of the jeep on top of the warm engine.

Dec. 7, 44

Somewhere in France

Dearest

Somewhere in France and still going strong. Can’t say as I am too miserable either. You would be envious of my quarters tonight—a beautiful apartment—the conquering Army stuff.

I took a fireman’s holiday in Strasbourg a while back, what an experience. It reminded me of a wild west opera combined with Al Capone. A wee bit dangerous to stand in one spot too long. It is beautiful country, would like to make a peaceful tour of the country some day.

You should see my personal car now, a long low captured Mercedes Benz staff car. It will do over 80 km/hr. Picked it up beyond Senones a few weeks back. Leather bucket seats side curtains, windshield wipers, and a trunk even to carry my bed roll—solid comfort, what? Where it got good American gas it took off like a scared rabbit. Has a few bullet holes and shell fragments but is in good condition.

A rather noisy night , am having a slight disturbing factor. If anyone gives a long low whistle when I settle down to being a husband, don’t be surprised at my actions. Am liable to dive in a ditch full of water.

Good nite, sweet,

Am thinking of you

Love, Gordon

It’s interesting to me that every time Dad mentions that the place where he’s staying has been commandeered, he repeats the same line, “the conquering Army stuff.” I suspect he had some ambivalence about it all, however pleasant it was to have a roof over his head.

My favorite part of the letter is his pride in his captured Mercedes Benz. All the guys I talked to in Company C spontaneously brought up Dad’s car. Wallis, no fan of officers and especially of Dad, still did admire that car. It was the fanciest, most powerful car that all these rural boys who’d grown up in the Depression had seen. Dad painted a big US and white stars all over it so no one would mistake it as a German officer. It had a wonderful advantage over the open jeeps in the bitter cold. It was closed.

On December 8, they entered the battle for Lemberg.

[footnotes are over on the other substack that’s just for these posts.]

Your father's ability to find joys in hell never ceases to amaze me. The image of the car will stick with me.