I have often thought that living in Hyde Park during urban renewal must have been so overwhelming with the mental map vanishing. When I’m walking along, I don’t think often about turning right on Cornell Avenue particularly. I automatically turn right when I see the white terracotta on the corner of the building there. Urban renewal tore down that neighborhood mental map. Landmarks like the beloved Hyde Park Hotel with the Tiffany ceiling in the dining room just evaporated overnight. The artist colony along 57th Street, Lake Park, and Harper was leveled. A goal of urban renewal was to eliminate population density and unsafe fire traps, so large rundown buildings built before 1918 just didn’t survive.

Walking by the corner of Lake Park, Harper, and 57th Street the other day, it dawned on me that, oddly, one landmark, the apartment building now called the Pepperland, survived.

I’ve been told that in the 1950s it was a home for a number of the Compass Players, including Mike Nichols and Barbara Harris. So, not only is it a physical survivor of Hyde Park’s bohemia, but it’s a spiritual survivor as well, picking up the nickname Pepperland years after the colony disappeared. Pepperland after all is the cheerful paradise under the sea where Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band lives in a yellow submarine. I find it more than a tad weird that the conglomerate that controls much of Hyde Park real estate made the name official.

One indication of Pepperland’s age is the number carved into the lintel over the doors. This door is “248.” That is the old original Hyde Park street number system that started numbering east/west streets from the lake shore, which was just two blocks away when it was built.

All the areas of Chicago had irregular numbering systems, especially in the separate towns annexed in 1889. A man named Edward Brennan tackled the problem. By 1909 the City Council had haggled their way to the system Chicago has now, which radiates outward from the corner of State and Madison and aligns all the numbers of all the blocks to help people navigate everywhere in the city. This step seemed relatively simple until the day all the new numbers became official. Two million pieces of mail didn’t make it to their destinations.

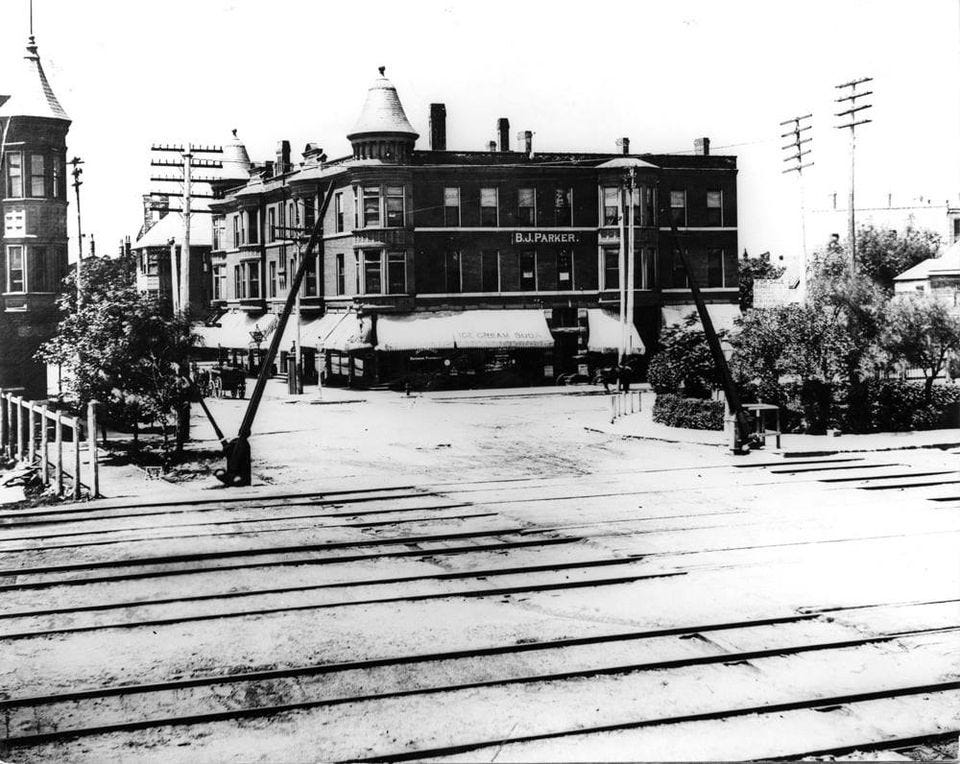

The building’s corner turrets right next to the tracks make it a landmark at least on my mental map. For instance, I immediately knew I was looking at old Lake Park between 57th and 56th Streets in this photo from the mid 1950s because the Pepperland turrets peek out on the corner in the back left.

That row of buildings on the right replaced the South Park Train Station that had once stood there. I talk about that in the cable car article.

The Pepperland was there before the tracks were raised. That happened for the 1893 World’s Fair. People needed to pass under the tracks to walk from the main buildings in Jackson Park to the refreshments and entertainment on the Midway. They passed under the tracks and the north/south streets. The streets returned to ground level but the tracks stayed raised.

This photo was taken just before the tracks were raised. The Pepperland is the one on the left. Turrets on the corners of buildings and bays that jutted out were popular in the 1880s and 1890s. They increased air circulation and sunlight in the era before air conditioning and commonly available electric lights. It must have had great views of the lake from the turrets before the tracks were raised. The building in the center of the photo held a popular restaurant under those awnings. It started with B. J. Parker’s in the photo. In the 1950s, it was the Continental Gourmet Restaurant. Jascha Heifetz was the first name in the guest book when it opened. It was forced to close in 1956 when the building was condemned. It was beloved and people in the neighborhood kept asking Webb & Knapp (the urban renewal developers) if there was some way to save it. U.S. Senator and Hyde Parker Paul Douglas asked if it could be saved. Mysteriously, the B. J. Parker building was torn down and the Pepperland wasn’t.

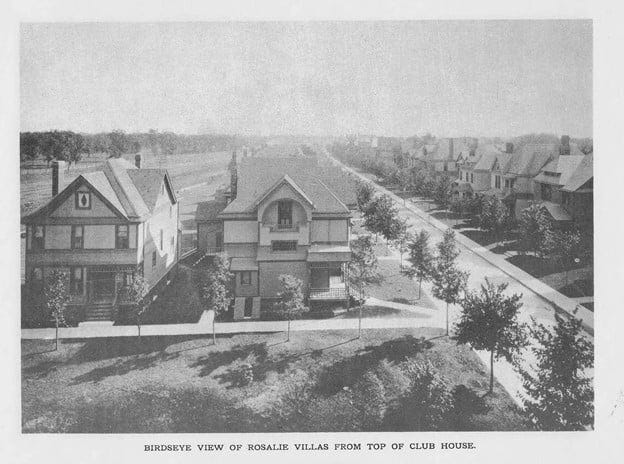

It seems to have been built around 1889. The first reference I could find was 1891. The reference I found is to the death of John Stillman Langworthy, a resident, who had served for 24 years as Deputy Controller of the Currency of the United States. He seems to have retired there to be close to his son who lived around the corner at 5755 Rosalie Court. It was known for most of its history as the Rosalie Flats, cashing in on the fame of the Rosalie Villas that lined Rosalie Court between 57th and 59th. The area was once quite elegant.

The Rosalie Villas were the brainchild of Rosalie Buckingham. Her grandfather made a fortune when he signed a contract with the new Illinois Central Railway to be the exclusive grain elevator for all of the railroad’s warehousing for the next 10 years. Even though Rosalie’s father died young, the family prospered. Rosalie studied music, traveled in Europe, and was Chicago high society. She put on harp concerts for charity. As she neared the age of 30, Rosalie decided to become a property developer. In 1883, she bought two undeveloped city blocks (“dark prairie soil” as her brochure said) from 57th Street to 59th Street near the IC tracks and hired Solon S. Beman, who had just planned Pullman.

The plan was for 42 villas (villa meant no rooms for live in servants) and smaller artists’ cottages. It included landscaping, a park, infrastructure development (sewer, paved street, sidewalks, lighting) and, on 57th Street, a three-story clubhouse on one corner and across the street an inn, café, and music hall with a business block with all the conveniences—drugstore, grocery store, reading room. The plans announced in an 1884 Tribune article called for ornamental granite and wrought iron arches on 57th and 59th as the proud owners entered the street, fountains in the park, and shade trees. Beman drew up design standards, which is why the street has a similar feel, though it had several architects. Most of the houses were set back the same distance, with a driveway leading to a stable behind the house. The idea was that these would be lovely retreats, conveniently right by the IC station and cable cars and cooled by lake breezes. Jackson Park was just across the tracks.

The houses sold quickly—and Rosalie was soon out of the real estate business. She married Selfridge in 1890, who moved them to London to build his department store—a saga made famous by PBS.

The Pepperland might still be the Rosalie Flats if it wasn’t for the Great Street Name Change in 1913. Because of the annexation of several suburbs, the city was riddled with duplicate names. After solving the problem of house numbers, the city council decided to fix the name problem. All the east/west roads would be STREET. All the north/south ones would be AVENUE. Of course, downtown got to keep their names, so Madison, Washington, Jefferson, Monroe, Jackson, Elm, Oak, and Cedar in Hyde Park had to change. The city fathers hunted for men worthy of getting streets named after them—people like Timothy Blackstone, President of the Chicago and Alton Railroad, whose widow had built the library in 1904.

It wasn’t just the duplicate names, though. The city council decided to knit the city together by calling discontinuous bits of road by the same name if they aligned. That is, if a street ran north/south at 1500 East, then all of the segments at 1500 East had to have the same name whether they connected or not. Rosalie Court was at 1500 East. So was Jefferson. It seemed easy enough to call all the segments Rosalie Avenue, but businesses on Jefferson protested loudly. They did not want to have a woman’s name. The city fathers suggested William Rainey Harper instead. The dynamic first president of the University of Chicago had just died. The protestors agreed and Harper Avenue was born.

Personally, I’d have found Harper a different street. University or Maryland were new names and no one seems to know why Maryland got chosen.

It’s sad to lose the memorial to Rosalie Buckingham’s unique and lasting vision. Her street is so pleasant to walk down at all times, but it comes into its own for the thousands who flock there every Hallowe’en.

Thank you for this wonderful slice of Hyde Park history!

Wonderful information! Thankyou