As anyone who follows this knows, I’ve been wrestling with the vast enterprises and sidelights of Lorado Taft’s career, but one of the most interesting to me is his support for anyone who felt the calling to create—in particular those struggling to overcome obstacles.

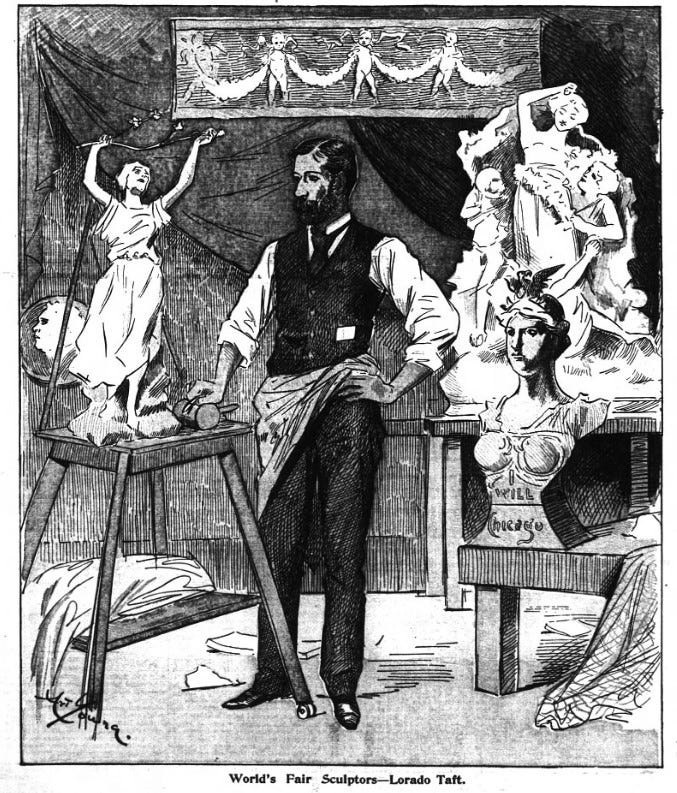

Taft himself arose far from the centers of art, but he felt blessed to have gotten the opportunity to study for years at the Ecoles de Beaux Arts in Paris, where he learned excellent technique and grew his distinctive “Parisian” beard. He’d made his way back to Chicago in the 1880s and found a steady income teaching modeling at the early Art Institute of Chicago. Soon the city was engulfed in the preparations for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

He quickly got a contract to provide the statuary and friezes for fellow Chicagoan William Le Baron Jenney’s Horticulture Building. Every building at the fair had elaborate ornamentation. It was an explosion of the arts in America.

Daniel Burnham, the fair’s impresario, quickly hired Taft for a second essential task. Sculptures were arriving at the fair as small clay models. They needed to be enlarged to the towering scale of the fair, executed in staff (a combination of cement, plaster of Paris, and hemp fibers that could be carved and molded), and then installed. Taft had the technical training from his years in Paris. He set up shop in the immense greenhouse space of the Horticulture Building and quickly realized he needed help. He went to Burnham to ask whether he could hire people from his Art Institute classes to help. After all, more established artists were all at work on their own projects. Burnham replied, I don’t care if you hire White Rabbits if they get the job done.

Taft hired a number of assistants, particularly his students who needed the income. A group of six women in their early twenties embraced the label White Rabbits. They were Janet Scudder, Julia Bracken, Carrie Brooks, Ellen Copp, Bessie Potter, Nellie Walker, and Taft’s sister Zulime. Most of them lodged in an inexpensive hotel near Jackson Park, possibly the one at Dorchester and 61st. They were paid $5 a day, and $7.50 if they worked on Sunday.

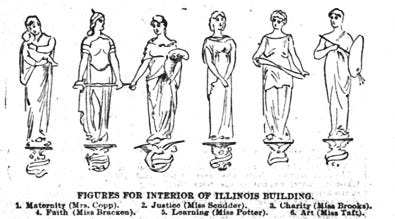

In addition to assisting him, Taft helped them get their own commissions. For instance, the White Rabbits together took over the series of sculptures inside the Illinois Building from Taft.

In December 1892, the Inter Ocean, whose editor was a friend of Taft’s, provided a detailed portrait of the White Rabbits.

Julia Bracken from Galena, the daughter of an Irish railroad worker, was the 12th child out of 13. She ran away from home at 13, got a job as a domestic servant with a family that recognized her talent. At 16, they paid for her classes at the Art Institute. At the fair, Taft handed over the commission from the Illinois Woman’s Exposition Board for “Illinois Welcoming the World.” Her statue was later cast in bronze and still stands in the state capital in Springfield. The Inter Ocean described her as “small, sweet, with dark hair and deep somber eyes.”

Bessie Potter was able to afford her tuition only because Lorado Taft paid her to work as a studio assistant on Saturdays so the fair was a big boost in income. She created the embodiment of Learning for Illinois.

Zulime “Tetie” Taft was Lorado’s sister who had moved to Chicago to pursue her art career after years of tending to their mother in her final illness. She created the statue of Art for Illinois and got a commission from Burnham for “Flying Victory.”

Janet Scudder from Indiana discovered her love of sculpture by carving butter before finding her way to Taft’s classes. In addition to a statue of Justice for Illinois, she created the Nymph of the Wabash for the Indiana building.

Carol (Carrie) Brooks was the daughter of portrait painter F. A. Brooks and the youngest of the White Rabbits. In addition to creating “Charity” for the Illinois Building, she created cupids for the central hall of the Arkansas Building.

Ellen Copp created "Maternity" for the Illinois Building and "Pele" advertising the “virtual reality” experience of a Mount Kilauea eruption on the Midway Plaisance. The 24-foot-tall statue of Pele was promoted as the "largest statue ever made by a woman." She also did a bronze relief portrait of Harriet Monroe in the juried Palace of Fine Arts and a bronze relief portrait of Bertha Honore Palmer for the library of the Woman’s Building.

The White Rabbits became an attraction. People working on building the fair would grab their lunch in the Horticulture Building to watch them work. Zulime thought she shook at least 45 governors by the hand in the process. One of the White Rabbits recalled that winter. The winter of 1892-1893 was one of bitter cold and deep snow. They waded through waist deep drifts to reach the building. One morning they arrived to find that a storm the night before had proved too much for the huge glass roof. It had crashed down. They confronted crushed clay figures, broken glass, and snow. Nothing could be salvaged, but these were resilient women. They started over.

Taft supported anyone with a passion for creating art. At the fair, two of the assistants were Charles Mulligan, an Irish immigrant who had started out in the stone quarries of Indiana before making his way to Chicago, and Leonard Crunelle, a French immigrant who encountered Taft while working in the Illinois coal mines. They became lifelong associates. Although the number wasn’t large, Black students do appear in some photos. One of them was Robert Thomas, who was identified in 1898 by the Inter Ocean as a well-known artist from San Francisco studying with Taft. Art had transformed Taft’s life and he dreamed of creating the same opportunity for others.

Urban Renewal Talk Now Posted

Unfortunately I had unstable internet so there are a couple of unexpected silences and a missing sentence here and there.